Excerpt

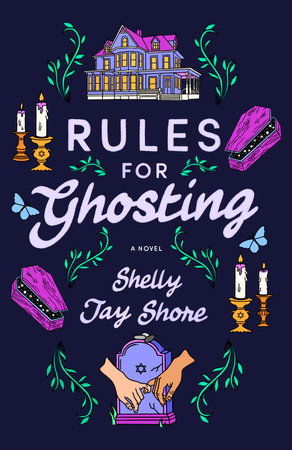

Rules for Ghosting

Twenty years agoIn the showroom, the caskets are arranged with care, from the gleaming mahogany to the sturdy pale poplar with the embellished lid.

Ezra has touched them all, ranking them by comfort and scent, how the fabric feels against his skin, whether he can see through the tiny holes bored through the bases to allow the dirt of the burial plot to seep inside.

Clients linger in that room, debating this engraving or that one, crepe lining over velvet. They murmur over the prices, typed neatly on stationery and tucked into plastic frames, each containing a handwritten legend: each casket has been built to the highest standard of kashrut, in accordance with jewish law. The script is his grandmother’s, graceful and sloping, every card carefully prepared at the kitchen table while Ezra watches with his head on his hands, lulled into meditation by the smooth flow of her fountain pen filled from the indigo inkwells his zayde buys her each birthday.

“It adds a human touch,” Bubbe tells him, the cards spread out across the kitchen table as the ink dries. When Ezra looks closely, he can see the tiny imperfections where the ink has blotted, smudged. “That’s what people need when they’re grieving. They don’t want a factory funeral—they want to know that a real person, with a face and a name, came and took care of the person they lost. That they weren’t just thrown away.”

Ezra nods and lets her run her fingers through his hair, the curls his mother won’t let him cut thick and loose and falling to his shoulders.

Zayde props the lids open and encourages the clients to take their time, to think, to touch, to choose what feels right.

“The body must touch the earth,” Zayde says in his accented English, Polish still clinging to the edge of each word, as he leads Ezra and Aaron through the room. They trail after him like ducklings in his tall, thin shadow. Years later, Ezra will have a philosophy professor who lectures the same way and will imagine the life Zayde might have had, if the world had been kinder.

By the time he’s six, Ezra can recognize the names of his siblings and parents and grandparents and cousins when they’re written out in front of him. He has memorized seven books, he can count to fifty-six, and he can recite the rules of Jewish burial customs like a poem, learning them at his grandfather’s knees the same way he learns the aleph-bet and the colors of the rainbow. For a casket to be kosher it cannot be constructed on the Sabbath and it must be made of wood: no metals in the hinges or fastenings or handles; the linings must degrade over time.

Because the body must touch the earth.

When Zayde leads clients on his tours of the room, they drift without fail toward the shinier models, the ones with their bright finishes and soft velvet. But Ezra’s favorite is the flat pine box that sits away from the others. He likes the way it smells, lingering juniper and sandpaper instead of wood polish and wax. When he climbs inside and turns to lie on his belly, the pinpricks of light shining through the holes sting his eyes, just enough hurt to make them water and blur.

Aaron kicks him in the ankle when Ezra climbs out again, rubbing his eyes and complaining about the light. “The people in there wouldn’t be looking,” he says, rolling his eyes.

Zayde swats the back of his head. “Don’t kick your sister.” His voice has a gravelly rasp, and he rarely raises it. But his stern whisper is more commanding than their father’s shout.

“Yeah,” Ezra says, sticking out his tongue. “Don’t kick your sister.”

Aaron makes a face. Ezra makes one back. Zayde sighs, long-suffering, and turns up the sound on the ancient radio.

“Don’t tell your brother,” Zayde will tell him, with a conspiratorial wink and a second toaster waffle, “but if you were a boy, I’d hand this place over to you.”

Every morning, from the time he’s old enough to walk until the spring he turns seven, Ezra follows Zayde across the yard that connects their family house to the funeral home. Holding Ezra’s hand, Zayde unlocks the staff entrance, and Ezra trails after him as he walks from room to room, turning on lamps and adjusting thermostats, fluffing the drapes, checking on the eternal light in the chapel, making sure the little signs on the display room caskets are arranged just so. Once everything is arranged to his satisfaction, he leads Ezra down into the basement, where Ezra sits at the rickety staff table in the kitchen and eats a toaster waffle and watches his grandfather start the first pot of coffee, then sit down to read the obituaries.

“I could be a boy,” Ezra says, every time, and Zayde pats his head and tells him to eat, nudging the bottle of maple syrup across the table toward him with a conspiratorial wink. Extra syrup is a sacred secret they share.

Ezra tells himself that it’s silly to feel hurt over these dismissals. He doesn’t know how to explain how much he hates the long hair his parents refuse to let him cut, the skirts Mom insists he wear on Shabbat. Aaron gets to wear pants.

“I swear, sweetheart,” Mom tells him. There is an exasperation in her voice. She has sent him up to his room, the third Saturday in a row, with firm instructions: Change your clothes. “I am ready for you to be done with this phase.”

When he looks back, years later, Ezra’s never sure why he always turned to his grandfather—what support he was hoping he’d get, what he was hoping Zayde would say. Whatever it was, he never said it, and Ezra, reluctant and pouting, would give in.

The morning before Zayde dies, Ezra resists. He sits on the stairs and refuses to go to shul if he has to wear a dress. He wraps himself around the banister, arms and legs both, and ignores his mother’s attempts to cajole, guilt, and coerce him. Becca, just a year old, is squirming and fussy in her arms. It’s not until Dad threatens to change him himself that Zayde steps in.

“I’ll stay home today,” he says, stopping any argument in its tracks. “You go on.”

They go, Aaron the only one who waves at Ezra on his way out the door, and that’s what makes Ezra cry. He unwraps himself from around the banister and puts his arms around his knees, burying his face in them, crying like Becca does, loud and without rules. He is frustrated and confused and hurt, and not sure why.

Zayde sits down next to him, his bones creaking audibly. He pats Ezra’s shoulder. “Your mother isn’t angry at you,” he says. “But you should listen to her.”

Ezra wipes his nose. “It’s a stupid rule,” he mutters.

“Maybe,” Zayde allows. “But you still need to listen.”

Any other morning, it wouldn’t be a betrayal. But on this one, with his skin already prickling and his heart already sore, it was.

“You don’t understand,” Ezra says.

“Well,” Zayde says. “Why don’t you tell me?”

Ezra shakes his head. “No.” He pushes his arm off. “I don’t want to. I’m going upstairs.”

Zayde says his name, but Ezra ignores him. He stomps up the steps and slams his door behind him. Sitting down with his back against it, he listens for the sound of footsteps on the stairs and hears them, the heavy, weighted tread of Zayde’s gait. After a moment, there’s a knock at the door.

Ezra pushes more firmly against it, just in case, and doesn’t answer.

Zayde sighs. “I know that sometimes we ask you to do things you don’t like,” he says, the words chosen slowly, carefully, as they almost always were. “But it’s part of being in a family. Even when it’s hard.”

“Then maybe I don’t want to be part of the family,” Ezra retorts. “Maybe I’ll just stay here. By myself. Then I don’t have to do anything.”

There’s a smile in Zayde’s voice when he says, “That sounds lonely.”

“I don’t care,” Ezra says. “I just want to do what I want. And I want you to go away.”

On the other side of the door, Zayde takes in a breath—and then sighs. Ezra holds his own breath, waiting, because he knows, knows, that he’s said something cruel.

A few seconds later, Zayde’s footsteps fade down the hallway.