Excerpt

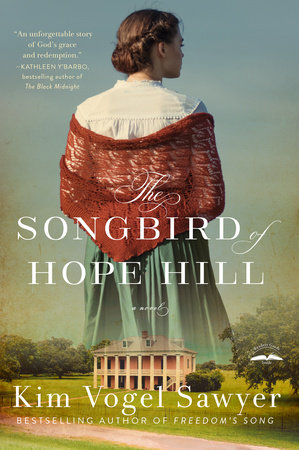

The Songbird of Hope Hill

Chapter One Early February 1895

Outskirts of Tulsey, Texas

Birdie Clarkson “Girls? Girls! Hour to open!”

Miz Holland’s grating call roused Birdie from a restless sleep. She stretched, and the ropes holding her hay-stuffed mattress squawked. She rubbed her eyes. When she’d gone to sleep eight hours ago, bright noonday sun was trying to sneak past the edges of the fringed window shade. Now those slivers of light were gone as nighttime cloaked the landscape. Her room was as dark as a tomb. Fitting, since what she did here made her feel dead inside.

She sat up and blinked several times, trying to discern the location of her bedside lamp. She didn’t dare break another one. The cost of replacement was too high. Slowly, she reached toward an hourglass-shaped object. Her palm encountered the cool glass globe of her lamp. She skimmed her fingers downward to the base, located the little tin of matches, and struck one on the flint. The flare pierced her eyes, and she squinted. She raised the globe, lit the wick, and put out the match’s flame with a puff of breath. Seated on the edge of her lumpy mattress, she stared at the lamp’s flickering glow and gathered the courage to rise. Dress. Go downstairs.

The other girls at Lida’s Palace didn’t bother lighting a lamp upon rising. They dressed in the dark. Birdie hadn’t been here long enough to learn the trick. But as soon as she’d donned her “work gown” and brushed her brown waves that Miz Holland called her crowning glory, she would extinguish her lamp. Partly to save the oil, for which she was expected to pay. Mostly because she had no desire to see her mirrored reflection attired in the bawdy costume . . . nor anything else that took place in this small room.

Noises—the patter of feet on floorboards, the creak of drawers or wardrobe doors opening and then snapping closed, a dull thud followed by a muffled curse—filtered through the thin walls separating her room from the others in the old hotel. Miz Holland’s girls were readying themselves to receive the evening’s visitors. To earn her keep, Birdie must do the same.

Pulling in a breath of fortification through her flared nostrils, she trudged to the corner and removed her gauzy, emerald-green, lace-embellished gown from its hook. Her stomach churned as she slipped her arms into the thin fabric sleeves. How many men would come tonight? How many would choose her? Since she was so new, she hadn’t yet become anyone’s favorite. Some of the girls bragged about the number of men who favored them over the others. Birdie had no desire to win such a contest. Then again, a girl’s popularity secured her continued sanctuary in Lida’s Palace. Would she be cast out if she couldn’t be, as Miz Holland put it, more friendly?

Birdie inwardly shuddered. She wouldn’t be here at all if hunger hadn’t driven her a week ago to knock on the door of her mama’s old school friend’s home and request a piece of bread or a bowl of soup.

In her mind’s eye, she saw the woman’s scowl change to recognition and then to a conniving smile as she appraised Birdie from her wind-tangled hair to the scuffed toes of her dusty shoes. Birdie experienced again the trepidation that had tiptoed through her at Miz Holland’s sly assessment. Why hadn’t she run away? If only she’d run away . . .

Bang! Bang! Bang!

The angry thuds on the door made her jerk. Her thumb caught in the delicate lace at the cuff of her right sleeve and tore it. Groaning in regret, she hurried to the door, frantically tying her sash as she went. She flung her door open and discovered Minerva, the oldest of the girls residing at Lida’s Palace, standing in the hall with her fists on her hips.

Minerva tossed her head, fluttering the feathers she’d woven into her fiery red braid. “Lida ain’t gonna hold breakfast for you. She says come now.” She twisted her lips in a sneer. “Look at you. You ain’t even combed your hair yet.” Her gaze dropped to the loop of lace dangling against Birdie’s wrist. “An’ it looks like you got a little repair work to do.” Her eyes glinted with humor. “Some fella get a little eager last night?”

Birdie’s face flamed. She shook her head. “No. I—”

Minerva rolled her eyes. “ ’Course not. Why would he? Spindly thing like you ain’t got nothin’ worth buyin’.”

Birdie pressed her chin to her shoulder and closed her eyes. If only it were true. Maybe Miz Holland would kick her out. But then how would she pay for travel to Kansas City, where Papa’s sister lived? Birdie still remembered standing with her aunt at Papa’s graveside six years ago, asking, “What will I do now? How will I go on without my father?”

Aunt Sally had put her arm around Birdie and pulled her close. “Dear girl, your earthly father’s gone, but you still have a heavenly Father. He’ll never leave you. You can lean on Him.” She’d then taken Birdie by the shoulders. “What do you think about coming to Kansas with me? You can finish your schooling and work with me in my dress shop. Maybe your mama will send you, if we ask.”

From the time she was little, Birdie had been handy with a needle. She could be a good helper for her aunt. Returning to a house where no kindhearted papa would sing songs with her or kiss her good night held no appeal. But when Birdie asked for money for the trip to Kansas, Mama threw a tantrum and called her selfish. So Birdie had stayed. Until the day Mama left.

Fifteen dollars and eighty-five cents. That’s what the station clerk at the depot said she needed to buy a train ticket from Tulsey to Kansas City. How many nights would it take to earn such a sum? And would Aunt Sally even welcome her, now that she’d—

Minerva’s derisive huff pulled Birdie from her thoughts. The girl flounced toward the staircase, feathers gently waving, and called over her shoulder, “If you’re wantin’ breakfast, better hurry up before Olga eats it all. That one sure can’t be called spindly.” Her laughter rang.

Birdie folded her arms across her aching chest and hung her head, shame weighting her. Hunger had driven her here. She’d hardly eaten a bite since she arrived. She didn’t want breakfast. She just wanted . . . out.

If only Papa hadn’t died. Then—

You still have a heavenly Father. You can lean on Him. Aunt Sally’s sweet words whispered through Birdie’s heart. Even though Birdie’s parents hadn’t attended church regularly, Papa had sung songs about God, who Aunt Sally called the heavenly Father. Birdie wished she could call Him her own. But if there was a Father in heaven, He’d surely turned His back on her the minute she crossed the threshold of Lida’s Palace.

The growl of wagon wheels on the hardpacked dirt driveway sneaked past the uninsulated walls. She broke out in a cold sweat. Customers were coming.