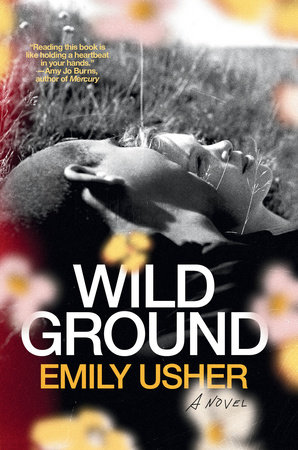

Excerpt

Wild Ground

1 I tell myself that the memory comes from nowhere. Not a memory exactly, but not a dream, either. More like a series of fragmented scenes, playing out behind my eyes in the space between asleep and awake. I haven’t thought of it all in years. I spend most of my time trying not to think.

I am back there, in that place they sent me to. Caged within the walls of a sprawling building on the edge of a spa town known for middle-aged women in cashmere twinsets and quaint cafés that serve overpriced cream teas. Except it isn’t a spa. It’s a unit, intended for people like me, people with dead eyes and messed-up heads and teeth falling out of faces.

Whenever anyone asks me what my name is, I say the same thing. Chrissy. My name’s Chrissy. The nurses exchange a look, pat my arm, scribble something down on their clipboards. I know it isn’t my name, of course I do. But every time I look in the mirror it’s her I see. My mam. And then, inevitably, I lose it, lift up my fist, smash it against the woman staring back at me. The mirror doesn’t crack, Chrissy just stays there, mocking us both. So I fling myself at her again, fling anything I can find, until eventually there are arms on mine, lifting me up, out, down, sinking a sedative into my skin.

The memory shifts so that I am in the common room, sitting in a semicircle with the other inmates. Except they don’t call us that. “Service Users” is the term they use, as if we have any say in being there. Some look near enough normal, like they might not seem out of place ordering a scone and an Earl Grey only a stone’s throw from where we’re all locked up. Others are in a bad way, their features swollen, their skin sallow, ravaged by the life they’ve led.

The telly is on, as it always is. We stare at the screen, but I am the only one watching it. A documentary about a rainforest, far, far away, plants of every size and color.

You know, I say out loud to no one in particular, a quarter of all medicines start off in the rainforest.

No one says anything back, although a few shift uncomfortably in their seats, cast nervous glances my way. Someone behind me clears their throat.

Almost every drug on this earth comes out the ground.

All right, Jennifer, the nurse sighs. Quieten down, please.

I ignore him, set my attention on the lass sitting to my left. She can’t be much older than me, her skin gray, the inside of her elbows covered in tracks that she doesn’t bother to hide. It’s a seed, I say, nodding at the marks. It starts with a seed.

She edges away from me, folds her arms over her chest. I smile to myself, turn back to the telly, watching a utopia of reds and yellows and blues unfurl on the screen, soaring trees and mad fauna.

Papaver somniferum. The flower of joy.

The lass looks up at me coldly. What yer goin on about, yer crank?

Poppies, that’s all they are. Same flower everyone sticks on as a paper pin fer Remembrance Day. When the petals fall away, I say—lifting my hands in the air and then letting them float down to my lap—they leave behind a pod, and inside it there’s a black, sticky gum.

That’s enough, Jennifer. The nurse presses a hand firmly on my shoulder. My eyes move back to the screen, but still I am talking, remembering.

And they take that and they mix it up, mix it with all sorts of chemicals and shit, I carry on, shaking the hand off, addressing the room now. Sell it on and then sell it on again, until eventually it reaches us lot, people like us, who’ve got nowt else to live fer.

The nurse moves around to my side of the sofa, grips me hard by the elbow. I try to pull away, but another one has joined him now, dragging me to my feet.

See, they say green is one thing, I call over my shoulder as the two of them lead me out of the room by force. They say it’s white and brown and all that other shit that’ll put you in t’ground. But it’s bullshit, see? It’s none of them things. What hurts is

people. People you love, you know what I’m sayin? They’re the ones that can mess you up. They’re the ones that will ruin. Your. Life.

I open my eyes with a start, my lungs empty, my mind swirling in a terror thick as tar. Squeezing my hands between my knees, I begin to count. To ten at first. One hundred, one thousand. I count the movements of each of my limbs as I climb out of bed, count the steps to the bathroom, the turn of the shower tap, the cracks in the tiles on the wall. The tip of my tongue runs along the surface of each of my teeth, counting, counting. Tallying and calculating, filling my head with nothingness.

That same day, I see Denz again.

2 I don’t recognize him at first. Or perhaps that’s not quite right. Perhaps it’s more that I hope he is someone else. He hovers in the doorway of the caff, watching the blood drain from my face. The familiarity of his outline turns me to stone. The broadness of his shoulders, the thick neck. The scar under his eye that cuts across the dark plane of his right cheekbone. Danny used to think it was the shit, that scar.

Minutes pass, or maybe just a split second. Fionnoula must have been talking to me because the next thing I know, she’s there in my ear.

Jen. Je-e-en? Are you still with us, love?

I steady myself on the counter, clear my throat. Sorry, Fi, what was that?

Denz is walking toward me, although I can’t bring myself to meet his gaze again. Instead I act as though he’s no one, except we both know it’s too late to play that game. It’s only when I take over the tea he ordered that he looks straight at me and says it out loud.

Cheers, Neef.

He uses that name like a weapon. A lifetime has passed since anybody called me that. But there he is, saying it like nothing has changed at all.

We don’t speak again, but I can feel his eyes on me. When he leaves the caff that afternoon, I have to hold myself back from following him, letting him lead me like the Pied Piper toward the person I used to be.

He comes again the next day, walks right in like he owns the place, puts a fiver on the counter, asks for a tea and then sits down, doesn’t even wait for the change.

Still like to act the big man, I see, I say as I slide the three pound coins back across the table to him. I put his tea in a paper cup but he doesn’t take the hint to leave. Instead he looks at me steadily, a spark of something dancing in his eyes. Denz always hated me, could see right through me, knew what I was before I had even become it.

Still got as much mouth as you always did, he shoots back.

I ignore him, go back to the counter, pretend to be busy even though it’s dead in there. The minute the clock hits four I turn the sign on the door to Closed, make a big show of it so he can’t pretend he hasn’t seen. That’s when he stops me.

Neef, can we talk?

For a second I freeze, steadying myself against the doorframe. There isn’t anyone here by that name, I say, enunciating my words, not dropping a single

t or

h. So I suggest you f*** off elsewhere.

He does nothing more in response than give me the same slow nod that I despised all those years ago. Then he leaves without another word.

Danny would be ashamed of me if he’d heard how I’d spoken to him. He’s still my dad, he would say, his jaw set, his eyes scalding. Whatever you think of him, he’s still my dad.

Yeah, I’d bite back, but he’s no one to me. He never was.