Excerpt

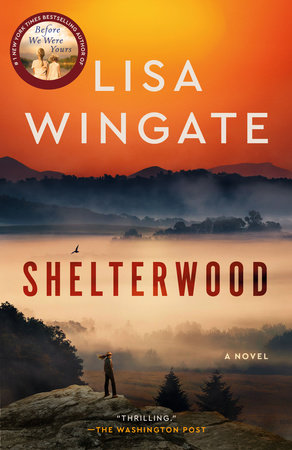

Shelterwood

Chapter 1Valerie Boren-Odell, Talihina, Oklahoma, 1990

When our ancestors first came to southeastern Oklahoma one of the first things they set their eyes on were the beautiful, forested Winding Stair Mountains. They are our Plymouth Rock, our Mississippi River, our Rocky Mountains, our Pacific Ocean. —Ron Glenn, Winding Stair Mountain Wilderness bill, S. 2571, congressional hearing, 1988.

Dear Val,

Why mince words? Dreams are wonderful things, but a single mother needs to be practical. Please tell me it isn’t too late for you to return to your job at the Arch in St. Louis?

Have you lost your mind? Talihina, Oklahoma? I can’t even find it on the map without putting on my glasses. No wonder you didn’t tell us ahead of time. Kenneth has been around asking about you, by the way. You know he thought you two were becoming more than just friends. I understand grief, my dear, but you can’t cling to it forever, and let’s face it, if you remarried, you wouldn’t have all these financial struggles. If you don’t call Kenneth to iron things out, I’m telling him where I sent this postcard to.

Put Charlie in the car and drive home. I know you have always been a free spirit, but it’s time to grow up.

—Gram

I read the postcard for the third time since grabbing it from the mail on my way to work, then survey the breathtaking valley below Emerald Vista turnout and try to decide how much trouble I’m in. My grandmother taught high school English for more than a half century. She does not end sentences with prepositions.

. . . where I sent this postcard to.

She is in a mood. This note is meant to tear me up a bit, and it does. To unsettle me slightly, and it does that, too.

I am in the backwoods of southeastern Oklahoma, where after a rain, the morning shadows linger long and deep, and the mountains exhale mist so thick it seems to have weight. The countryside exudes the eerie, forgotten feel of a place where a woman and a seven-year-old boy could simply vanish and no one would ever know.

A puff of wind slides by, unsettling the folder I pulled from my day pack to extract the postcard. A mockup brochure and a half dozen high-end paper samples tumble to the pavement and slide away like fallen leaves. I should chase them down, but instead, I stand frozen. My mind drifts all the way to Talihina, where a cheery yellow house offers the only acceptable daycare willing to watch over a boy whose mom’s new job will sometimes entail rotating days off and working odd hours.

Just go get him, I tell myself. Pick him up and pack everything back into the car and go. This is crazy. All of this is crazy.

Instead, I pull a slow breath. The morning air is thicker, greener, and warmer than I’m accustomed to in May. It smells of summer. Summer, and earth, and damp stone, and shortleaf pines. Different from St. Louis in a way that whispers something so compelling my heart quickens.

The yearning for wild spaces is as much a part of me as my father’s gray-green eyes and thick auburn hair. He fostered that passion in me even before a stint in Vietnam quietly severed my parents’ ten-year marriage and made the backcountry the only place he was at peace. Knowing him at all after that meant spending time in the woods, so as often as she could, my grandmother drove me from the Kansas City burbs to the Shawnee National Forest, where her only surviving son guided hikes and raft trips. Gram made those journeys seem like a gift rather than a burden, so I saw them that way, too.

I thought she, if anybody, would understand this job transfer from Gateway Arches in St. Louis to the newly minted Horsethief Trail National Park in Oklahoma’s Winding Stair Mountains. But now I wonder if she sees history repeating itself—another thirty-year-old parent running from pain instead of dealing with it. Another helpless kid caught in the tailwind.

Is this relocation a reckless escape attempt or a smart career move? The position here is a GS-9 level job. At Arches, developing programs and exhibits, shuffling tourists around patches of grass and concrete, I was doing what amounted to grade-level 5 tasks, which was all I could handle when Charlie was three and suddenly without a father. I didn’t have the mental space to care about career advancement. But it’s time now. This is my chance to step back into park law enforcement. I never thought I’d get the position at the new Winding Stair unit, and I still don’t know why I did. But here I am.

It isn’t selfish, I assure myself. It’s necessary. If Joel were here, he’d tell you to go for it.

Just the thought fills me with a bittersweet mix of warmth and longing. I wish he could share this stunning morning view. Joel liked nothing better than a mountain he hadn’t yet climbed. Nothing.

“Hey . . . your stuff!” The voice seems remote at first. “Hey, Ranger, you dropped your papers.”

I come back to earth and Emerald Vista overlook, where suddenly I’m not alone. From the path to a nearby campground, a spindly adolescent girl sprints across the pavement, snatching up my runaway brochure sample on the fly. She’s eleven, maybe twelve. A few years older than Charlie. Wiry with long, dark hair.

Clutching the folder to my chest, I gather the pieces still at my feet. When I straighten, the girl is on her way over with the rest of the escaped papers in hand. She’s dressed in raggedy cutoffs and a washed-out T-shirt that reads antlers bearcats baseball. I search my memory for where Antlers is located. Someplace farther south along the Kiamichi River. I’ve seen it on the map.

“Here ya go, Ranger,” she says with a childlike admiration that reminds me I’m wearing my Class A Field uniform for the first time since the move. My start at the new unit has been frustratingly slow, my daily assignments for the past two weeks alternating between familiarizing myself with park trails and facilities, performing menial office tasks, and stocking brochure pockets on shiny new notice boards. I donned the uniform, gear-laden duty belt, and Smokey Bear hat today to make a point. I’m ready to do the job I came here for. But once again I find myself tasked with the same busywork.

The girl draws back upon getting a full frontal look at me. “Hey, you’re a girl ranger!” She blinks as if a UFO has landed. One of the advantages of being tall—I can almost pass for one of the guys, but the guys at the station have been quick to remind me that I’m not. A female law enforcement ranger wasn’t something they’d imagined here at Horsethief Trail.

But this little girl likes it, and so I immediately like her. “That’s cool,” she says.

“Thanks.” I recover the paper samples, spreading them like a deck of cards. “Got a favorite? I’m working on print materials for the park’s official opening ceremonies.” More busywork from my new supervisor, Chief Ranger Arrington. You know, give you some time to get up to speed. He came just short of patting me on the head when he said it.

“Looks like the park’s already open,” the girl observes. “The church field trip bus just pulled right on into the campground down yonder after some kid upchucked all over the place. Nobody’s camped down there, but the gate’s not locked or stuff.”

“Opening ceremonies aren’t for a week and a half yet, but, yes, the facilities are already available to the public.” The park is an eclectic combination of WPA-era recreational areas built over fifty years ago and fifteen million dollars in additions and upgrades funded by the congressional designation of Horsethief Trail National Park.

“My grandma told me they were making all kinds of new trails and stuff up here,” the girl chatters. “She said she’d take me to see everything.”

“Great idea. It’s a beautiful time of year.”

“Except she can’t right now.” A hopeful look slides toward my patrol vehicle. “But somebody might take me around, since I’m stuck for the summer. In stupid Talihina. Where I don’t got any friends.”

She’s laying it on thick, but I nod sympathetically anyway. “I bet we’ll be hosting summer opportunities for kids, once we’re fully staffed here.” Visitor programs aren’t in my purview, but the cultural and historical features of the region include ancient earthen mounds left behind by prehistoric Caddo-Mississippian cultures, Viking rune stones that are either genuine or forged depending on whom you ask, French and Spanish treasure legends, rumors of hidden outlaw loot, Civil War sites, the 1830s-era military road, and the Horsethief Trail, by which stolen animals were moved between Kansas and Texas back in the day. “These mountains have a lot of history.”

“Yeah, my grandma knows all that stuff. She’s been around here since, like, forever.”

“Interesting.” Grandma might be a good person to meet, as I’m trying to acquaint myself with my new neighborhood.