Excerpt

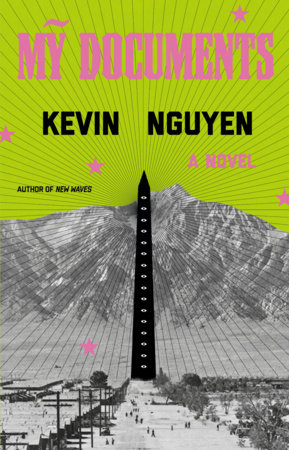

My Documents

Extended Family Bà Nội’s story had everything: history, conflict, romance, loss—all the elements of a compelling tragedy.

During the war, she’d been the one who kept the family safe. Whether it was bribing corrupt government officials or dealing with the sudden imposition of U.S. soldiers, Bà Nội paid off whomever and cooked meals for whatever foreigner, as distasteful to her as it was, if it meant not causing any trouble.

Her husband was a different story. He was a poet, a brave soul who never lied and held true to his beliefs. Not exactly ideal during a civil war, Bà Nội used to joke. But she admired his perseverance, even when his convictions put the burden of breadwinning and childrearing on her. Ông Nội made pitiful money teaching at the university. He was invested in the lives of his students, hosting late night “discussion groups” with them at the bar and returning in the early morning, just when Bà Nội was getting their own kids ready for school and herself for work. She loved him anyway.

Ông Nội had been warned by the police, who suspected he was distributing antiwar material. Which, of course, he was, despite Bà Nội’s pleading. Bitterly, she explained: a man would rather risk everything, including the livelihood of everyone he cares about, than be told what he shouldn’t do.

Saigon fell, and many of Bà Nội’s friends and extended family attempted to flee. What was the rush, though? The war was over, and the government she’d lived under had lost. But how much worse could this regime change be? The brunt of the violence had ended, and Bà Nội imagined that it would just be a new set of bureaucrats looking for payouts, and soldiers in different uniforms tromping around the streets. They could leave in time, and on their terms, rather than scrambling for the nearest exit. The French occupation of Bà Nội’s childhood had left Saigon with a number of cinemas, and with her a love of film. She hoped they could go to Paris.

The North’s sweep through the South had been more vindictive than she’d expected. The Communists seized all of her money and converted her savings into a new, worthless currency. Soldiers ransacked the home she had raised her four children in, taking everything of value, except for the small stash of jewels she’d hidden in a statue of Buddha.

Bà Nội felt foolish for not getting her family out sooner. Now it would take months to arrange safe passage out of Vietnam. She tried everything, but most of her attempts were thwarted by logistics or made unfeasible by cost. One arrangement involved purchasing a boat with a close friend. That ended in betrayal, the “friend” taking the vessel to sea without notice. Years later, Bà Nội told this story without a hint of anger in her voice. Maybe the decades since had softened her; maybe she just understood what was at stake. In desperate times, she said, the only thing left was family.

Eventually, Bà Nội recognized that getting everyone out of Vietnam at once was impossible. But vanishing one by one, that was less impossible. She schemed ways to migrate her children out of the country individually, so as not to be noticed. Paris was not an option without attendance at a French school, but the United States, perhaps out of American guilt, was easier. Her eldest son was granted a visa after enrolling in a university in the Midwest; another son she handed off to missionaries, who promised that he would have a rewarding and faith-filled life in the States. The next, a daughter, school age, was gifted as a temporary servant to another family that had been granted transit to New England. Each departure took something of her with them, every missing child reducing the breadth of what she could feel. By the time the third had left, Bà Nội’s spectrum of emotion hadn’t narrowed but washed out, like photographs faded by the sun. Even at the movie theater, where she had most enjoyed laughing and sobbing in the dark, her sensations felt diminished. Bà Nội told herself she would be restored when she saw them all again, safe.

The last of her children was four years old, too young to be sent off on his own. Bà Nội arranged an escape for her young son, herself, and her husband by way of a commercial fishing boat—a journey that she knew would be miserable and treacherous, especially with pirates so eagerly raiding ships now that the U.S. Navy had withdrawn. The hope was that the boat could make it far enough in the South China Sea to end up in a refugee camp in Malaysia, or perhaps Indonesia. This path wouldn’t take them to the U.S. directly, but for Bà Nội, it was drifting in the right direction.

The plan was to meet at the dock and leave together, as a family. The departure was late on a Tuesday evening, a getaway made less conspicuous by nightfall. But as the moon rose, Bà Nội still couldn’t locate her husband. She assumed that he was already there and took her four-year-old aboard. She scanned the deck, but Ông Nội was nowhere to be found. An hour passed, and he never materialized. Bà Nội pleaded with the captain to delay, but every minute they lingered increased their chances of getting caught. If she wanted to wait for her husband, the captain said, she could do it on land.

After so many failed attempts to flee, Bà Nội knew she couldn’t leave opportunities on the table. She hoped that Ông Nội might eventually find his way to the U.S., to reunite with them later, after she’d tracked down their other three children, and they could be a family once again.

Bà Nội spent the journey dizzied by seasickness, thinking furiously about her husband. How could he not have shown up? He was probably still in Saigon, drunk again, involving himself in the petty dramas of his pupils. Maybe that was all he ever actually wanted—to be swept up in the small, frivolous lives of young people, the desires of a coward.

It was months after arriving at the Galang Refugee Camp in Indonesia when Bà Nội received word about her husband. The day they were set to depart, police had seized Ông Nội at his university office. A naïve student had passed on his anti-Communist writing—some bad poems, barely distributed. In prison, he’d gotten sick and, with little medical support, had died of pneumonia.

Ursula teared up every time she heard this part of her grandmother’s story. It hit her in the gut: the strong matriarch who sacrificed everything for her family, making the unbearable choice of leaving her husband behind, and having to live with that decision for the rest of her days.

Throughout high school, Ursula wrote and rewrote Bà Nội’s journey. She kept getting rewarded for it. As a paper, it was the champion among final projects in an American history class, one teacher so thrilled with it that Ursula was given special merits by the administration at the end of the year. It was the personal statement on her college applications, which got her into several schools she had no business getting into with her middling GPA and average test scores. That same year, she won an essay competition writing about how her grandmother’s life made her feel, which came with a two-hundred-dollar reward—an extraordinary amount of money that Ursula immediately spent on a bag.

But Ursula knew she couldn’t use her grandmother’s story forever. Adulthood meant creating your own narrative, not regurgitating the details of someone else’s. Yet, by crafting and refining the tragic arc of her grandmother’s story, she learned something about what people liked hearing. Nobody wanted a tale about refugees where an entire family makes it out unscathed. For it to be compelling, to be important, there needed to be a sacrifice. Something had to be lost.

It wasn’t until Bà Nội’s disheartening prognosis that Ursula had started taking an interest in her grandmother’s history. To Ursula it seemed so dumb, so cruel, that a woman could overcome such tremendous obstacles and succumb to the same boring fate as millions of other people. That it was the most common variation, breast cancer, felt like an even greater insult.

The diagnosis had activated something in Bà Nội. Now she wanted to write her story down, from the beginning: growing up impoverished in Vietnam, the American war, fleeing, the long road to immigration. Hers was a life of constant and great escape. And now Ursula felt the burden of both being respectful to her bà nội’s wishes and trying to squeeze as much information out of her sick grandmother as she could.

“Why did you ask me?” Ursula asked. Though they hadn’t been close, Ursula was flattered that Bà Nội had wanted her help. There were other, older grandchildren, ones who were full Viet and spoke the language and spent more time with her.

“Because you are the writer in the family,” Bà Nội had said, as if there could only be one.