Excerpt

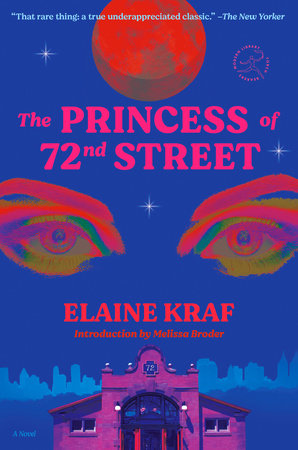

The Princess of 72nd Street

I am glad I have the radiance. This time I am wiser. No one will know. Perhaps it is a virus—a virus causing my being to expand and glow instead of causing nausea and weakness. It is not what they think it is. Usually they treat this lovely feeling with drugs. Weren’t they surprised when the lithium salts didn’t work. All of them so sure they could call it manic-depression and level it with those salts. I fooled them. Finally it was cured in the usual way. In fact any feeling can be cured if you want to get rid of it by shooting up large amounts of Thorazine, Stelazine, and more recent derivatives into the buttocks or ass or bottom or gluteus maximus.

What a fool I was to go there all by myself of my own free will last time and live in the green painted room until they made certain that the radiance was gone. When I have this condition it is hard for me to follow directions, difficult to keep to schedules, to play follow the leader. When they cure it with the drugs that make my limbs heavy and my mind stupified, I cannot laugh suddenly or cry or even dance. It is like something is binding me. But I can follow orders very well. I can do whatever I am told. Then they say, she is over the acute stage. I am praised and the dosage is lowered. Finally I am released. I come out into the world with correct patterns of speech, and for a while I see a psychiatrist and take my maintenance dosage and look for a job in the newspaper. It is a pretense. The realization of who I am comes back to me. Not the radiance. You see, the two don’t always go together. I am the Princess of 72nd Street. This is a fact. Something I know deep inside but only mentioned during my first and second radiance. They want me to believe that a radiance follows some terrible rejection or loss of self-esteem and is some kind of defensive device creating chemical changes and loss of boundaries. They are wrong. I have gotten the radiance when I have been depressed about something and also when things were going along in their normal way. The truth that they refuse to admit to is that there is no pattern. None.

For example, I was visiting some friends in the country, somewhere covered with green, somewhere people are proud to live because it is covered with green grass instead of ordinary pavement. This is something I don’t understand—arrogance about life near trees and birds and green grass. I’ve tried. All that green was so dull, so stifling. I had the feeling that the green was sucking up all the air and then spitting out something sickly sweet. But they felt that I should be happy to get away from the city which they think is noisy and smells bad. And so I made the appropriate remarks. Somewhere there must be a book full of them. I learned those things a long time ago. In the evening, to my horror because I hate eating outside, my friend’s husband decided that a barbecue was what I would like. A large lump of meat was placed on some tin contraption, and he kept turning it over with an air of self-importance if I remember correctly. I sat around getting nauseated. I like little pieces of meat eaten quickly inside. My friend Melita was doing things to radishes and lettuce, running inside and outside and upstairs and downstairs, as though it were an occasion. She was wearing a pair of the earrings that she makes in the cellar. Melita has a tiny face and a large tall body. The earrings were long almost shoulder length silver loops with three purple plastic triangles just brushing her shoulders. I’ve never cared for my friend Melita but we think we like each other. It’s a friendship that has been going on since she chose to be my friend at an art school where we were studying to be great painters.

In those days Melita painted plums—three plums on a horizontal canvas, or one plum all alone on a square canvas, or plums scattered about, or plums cut open, and occasionally plums on a white plate. When plums were out of season Melita got upset and sat in a corner of the studio. She said she didn’t understand life or her own feelings or the feelings in the paintings around her. She over ate during these times, and pimples came out on her back and face. Once I suggested to her that she paint the soul of a plum. She was very suspicious and thought I was being condescending, which I was, but I was also trying to help her pimples. Melita thought about it for a long time and began stretching enormous canvases on which she painted what looked like a sky with a gigantic purple moon. She painted so many of these that she became exhausted and got mononucleosis. Everyone got mononucleosis in those days, but it was probably other things. I think we learned how to induce and produce mononucleosis at will. It was an ultimate solution. Everyone understood, having had it, and everyone was kind and expected nothing. You could have mononucleosis as long as you wanted to. It was better than the way they used to get tuberculosis in the old days. No one died and yet it was long and languorous.

Melita looked beautiful only when she had mononucleosis. She became slim with her whole body going together without lumps of fat or pimples, and her eyes became large and luminous. That is when Peter noticed her—this very same Peter who was turning the lump of meat over and over and now tended to ignore Melita except when they had company. At that time Peter used to go into the woods to shoot rabbits and ducks which he quicky painted in large sure strokes so he was finished in time to eat them. He was known as the genius, the Manet, of our entire group. No one else could paint so quickly with each stroke being the right choice like a miracle. One day for no reason Peter couldn’t paint anymore. He couldn’t remember how he had been doing it. He stopped hoping for it to come back and studied art history. Even now he teaches courses in art history. His specialty is Vermeer. I don’t know why. Vermeer has nothing to do with ducks or rabbits or even plums. No one ever mentions Peter’s old paintings. Melita is self-conscious about painting in front of Peter so she makes peculiar jewelry and secretly paints plums when they are in season. I suspect that Peter knows about it, but he never talked about it, at least not then. Peter couldn’t stand the sight of a plum. Melita explained to me that she must be very careful because he can smell a plum miles away and breaks out in hives.

They enjoy swimming in their pool. This is something else that I never understood. I think, in fact, that it is crazy, this moving back and forth in water. Even though we are related to the fish in the embryonic stage, I still think it is unnecessary. I watched them the morning after the barbecue. In the middle of the night Peter had come into my bed. I told him that I love Melita too much to do such a thing. It was easier that way. Peter sulked but finally said that he understood. He understands nothing—nothing of my peculiar morality, nothing of my status as Princess of 72nd Street, and nothing of the irrelevant fact that he repels me. The next morning he was holding Melita’s wet body near the edge of the pool. I don’t swim, just sit dangling my toes in the water. I was watching them swimming back and forth like crazy people with their lips getting blue, both of them thinking there was something good in this. I tried to think of what it could be: gills, legfins, primeval slime, uric acid. Was there some sense of accomplishment they felt? Was it a purely physical sensation, or simply a habit? It certainly made them look ugly and goose-pimpled and blue-lipped and out of breath and wrinkled and pathetic.

Sitting there and watching them I unexpectedly got the radiance. My body felt light as a flower, my breathing itself gave me great pleasure, and my hair seemed to fly up and outward like wispy silk. I smiled and then laughed. Peter and Melita looked up and laughed also. Such musical sounds. Little bells. I began to run around and around on the hot dry grass and to look straight up into the sun. The sun understands me. The sun is a wine fire with strange threads of blue. It roars its comprehension of everything I am. I knew that. Peter and Melita became two exotic wet water flowers simple and spreading out white petals. I embraced both of them. Neither of them liked this. They know me as someone who is not demonstrative. Peter muttered something about how the country air was doing me good and Melita asked if I was hungry. People like to pretend that radiance is something else when they see it. I hardly heard them. I was leaping and singing and reciting poetry—the poetry of sun and fishfins and balloons. I jumped into the pool and lay there for a long time, smiling at the sun and letting the water fill my ears like it rushes into a seashell. I felt an obstruction and took off my bathing suit, letting it fall to the bottom. I am the water.