Excerpt

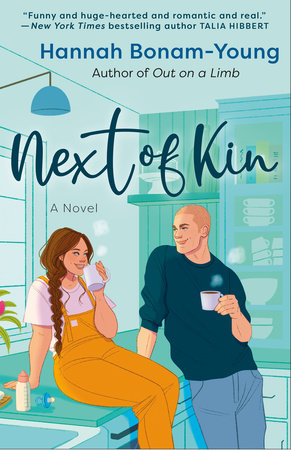

Next of Kin

One My phone rings, flashing a number that immediately sends a chill down my spine. I follow my instincts, ditching my cart and spot in the checkout line to find quiet in the grocery store’s bathroom, which, thankfully, is empty.

“Hello, this is Chloe.” My voice is already shaking.

“Hi, Chloe, this is Rachel Feroux calling from Child Protective Services. Is this a good time to talk?”

I close the toilet stall and lock it behind me as an all-too-familiar feeling of dread creeps into my chest. I paw at my collarbone with my free hand. A nervous rash is most likely already spreading. “Sure.”

Connie . . . it has to be Connie. She’s hurt, or worse. Why else would CPS call? I haven’t heard from a social worker in over six years.

“Okay, great.” Rachel clears her throat, then seems to brace herself with a loud inhale. “In your file, it states that you’re open to your birth mother contacting you. Is that still accurate?”

Do I want to know? “Yes . . .”

“It is sort of an unusual call, I suppose. Your mother . . . sorry, Constance. Constance has put in an urgent request that you visit her. She’s at the hospital.”

My body goes entirely still, and the blood pumps slower in my veins. As much as I have tried to distance myself from her, the need for Connie to be okay still sits lodged in my throat.

“She has just, entirely unexpectedly, given birth.”

“I’m sorry, what?” I fight for my next breath.

“Your mother had a baby.” My palm hits the stall’s wall before my back does, and I slide down to sit on the floor.

I’ll burn these clothes later. “No. That—but—

what?”

“I understand that it must be a lot to process. I wish there was a way for me to deliver this news that wouldn’t give such a shock. I know that it’s been over ten years since you have seen or heard from your mother.”

That is not

entirely true. There were plenty of times in high school when she showed up without my adoptive parents’ permission, and I never told.

“Is she— Is Connie okay?”

“Yes, she’s fine. A colleague of mine is with her right now. The baby was premature. The doctor who called us earlier said they will make a full recovery, probably after a two- or three-month NICU stay. The baby . . . will not be placed with your mother. We are looking into different care options.”

Colleague. Placed. Care. Social workers are all over this—why would Connie want to see me? Wouldn’t she understand how messed up that is? To need me while she sends another kid into foster care?

No, not just another kid . . . my sibling. She clears her throat. “Constance has listed you as a possible caregiver. She’s willing to sign over her parental rights to you. If not, the baby, after making a full recovery, will be placed in foster care.”

I pull the phone away from my face and stare blankly at the screen for a moment. I must have a bad signal or be imagining this entirely. A possible caregiver? For a baby.

Me? “But . . . I’m twenty-four.” I’m not sure why that’s the thought that escapes when there are about two thousand others bouncing around in my head, but for whatever reason, it’s what comes out. Twenty-four, recently graduated, no idea what I’m doing . . . Hell, I had been crossing my fingers that my bank card wouldn’t be declined for my groceries.

“Chloe, I understand that this is a lot to ask of you. Especially considering your . . . distant relationship with your birth mother. However, it’s only appropriate that we follow up with each possible contact she provides. You have every right to say no, and there could be visitation options with your sibling if you were to want that.”

I gasp softly as an undeniable rush of joy curves my lips into a smile, another thought breaking through the heavy silence.

I have a sibling. I’d have given anything for a sibling growing up, someone familiar and known. Someone to love and be loved by unconditionally. “Would I even be allowed?” I ask hesitantly. “If I wanted to?”

“That would require a much larger conversation . . . one that may be best to have at my office.”

“Yeah . . . okay.”

“There would be lots to discuss. I think, right now, we should just digest this news.” Rachel’s voice remains cool yet determined.

“Right.” I pinch the bridge of my nose. My eyes are closed, but the room keeps spinning.

“Constance

is asking to see you regardless.”

“Okay.” I don’t know if it’s the prospect of seeing Connie or the thought that she chose not to reach out before now that causes my lips to tremble, but either way, they do.

“But to be perfectly clear, the choice is ultimately yours.” Rachel’s gentle confidence reassures me somewhat.

“Yeah . . .”

“How about I give you the phone number of my colleague who is with Constance now? If you decide you want to see her, you can get the information from her. Then we can go from there, whatever you decide.”

My head aches and pounds, feeling like it would on a relentlessly humid day before a thunderstorm.

After Rachel gives me her colleague’s details, I hang up the phone and press it into the space between my eyes. Focusing on that spot of slight discomfort, one I’m choosing to cause and not receive unwillingly, seems to help. I think of Connie, or at least the latest version of her I have in memory, and transfer that image to a hospital bed.

Sympathy swells despite my impulse to shut my emotions down and get out of this bathroom without causing a scene. I imagine the similarities between where she is now and the picture that used to sit on her bedside table. Our first photo together, taken as she lay in a different hospital bed almost twenty-five years ago. She had been alone then too and only seventeen.

My thoughts hold on my birth mother until an unwelcome memory rises to the top of the pile. I was four years old, waiting on an empty school bus that had already made a second loop back to my street. Sitting alone with the bus driver and my kindergarten teacher, I remember thinking that they both looked at me with the same expression my mom had when I’d fallen out of a tree a few days before. I asked myself why they did that—I wasn’t hurt.

“Mommy didn’t mention any plans she had for today?” Ms. Brown had asked me.

“Nope,” little me answered.

“Do you know your grandma’s phone number? Or where she might work?”

“I don’t have a grandma. I have an uncle, but he lives on a big boat.”

“And your . . . dad? Do you know your dad’s name, sweetie?” Ms. Brown was making me nervous, and I wanted my mom. Mostly so I could show her the artwork I’d made and ask if I had a dad like my friend Sara did. Sara’s dad seemed nice. Maybe, I had thought, he could be my dad too.

“Nope,” I answered.

“Okay, all right. Well, I think you and I are going to go on a little adventure today! Would you like to see where Ms. Brown lives?”

“Don’t you have a dog?” I asked.

“Uh . . . yes, I do.”

“I don’t like dogs. They’re stinky.”

“Well, how about we put him outside and the two of us can play inside?”

Ms. Brown had taken me back to her house for two hours before CPS workers arrived and placed me in emergency care.

I’ve read in my file since—the one I was “gifted” on my eighteenth birthday—that the police tracked Connie down a few days later. She was high, drunk, and angry to have been found. I bounced around foster care for a year until my mom proved successful enough in her sobriety that I was able to move back in with her. I knew she had worked hard for that. Counselors, social workers, and teachers—they’d all told me how much my mom had worked to get me back.

I’ve never understood why they needed to tell me that, as if any five-year-old should be grateful to be with their own mother. As if I was a sobriety chip and not a human.

When Connie relapsed ten months later, my head was so filled up with forced gratitude that I felt worse for her than for myself. I should have been told I didn’t deserve to eat nothing but dry Froot Loops for three days straight—but I wasn’t. Instead, I felt sad for her. I still do.

Now, she’s brought another kid into this mess.