Excerpt

Painter in a Savage Land

INTRODUCTION

Unstill Life

“ONE HUNDRED AND TWENTY THOUSAND DOLLARS. LAST CHANCE,” said the auctioneer, peering around the crowded salesroom, his hammer cocked in anticipation. “At one hundred and twenty thousand—and down it goes!”

The hammer fell with a sharp crack. “At one hundred and twenty thousand dollars. Sold!”

To the auctioneer’s right stood a painting as unostentatious as it was enigmatic. Measuring just under six inches tall by not quite eight inches wide, the watercolor—an austere still life with apples, chestnuts, and medlars arranged on a plain white background—seemed somehow too small, too stark, to fetch such an extravagant price. These were not its only incongruities. There was no signature on the painting, nor had any information been made publicly available about the provenance of this previously unknown work, dated to the mid-1500s. Lost to history for more than four centuries, it had suddenly appeared, with great fanfare but little explanation, in a sale at Sotheby’s, the venerable auction house.

This was in late January of 2004, a time when art collectors, curators, and dealers from all over Europe and America had congregated in Manhattan for a week devoted to auctions of drawings by old masters. The annual event typically features, in the words of one industry journal, “a great deal of schmoozing, drinking, and malicious gossip,” but on this day the mood was sober and tense as buyers jammed into the salesroom, nervously fingering catalogs as they shifted in their seats or whispering in groups as they stood along the walls. Many of them were there to bid on the season’s star attractions: a group of twenty-seven natural-history paintings, including the one that had just sold for $120,000. These works, painted in watercolor and gouache over traces of black chalk, had been executed in the sixteenth century but only recently rediscovered.

The artist to whom they were attributed was as mysterious as the paintings themselves. For hundreds of years, he was little more than a historical footnote, his name mentioned only on the browned pages of a few old books and kept alive by a small group of specialized historians and collectors. The better part of his work remained unknown, the breadth of his interests and achievements unrecognized. It was only in the twentieth century, as more of his paintings were properly identified, that he began to gain wider fame and academic attention. Yet even today his life story is full of gaps and riddles.

This sale marked the first major discovery of his work in more than forty years. And while none of the paintings were signed, the bidders were obviously convinced of their authenticity. As the morning wore on, prices spiraled skyward on one small watercolor after another: $85,000 for a study of a dragonfly, a stag beetle, two narcissi, and a columbine; $95,000 for a gillyflower, two wild daffodils, a lesser periwinkle, and a red admiral butterfly; $100,000 for five clove pinks. The purchasers included private collectors and prominent dealers, as well as such august institutions as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. Dead for more than four centuries and for most of those years virtually forgotten, Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues was suddenly an artist very much in demand.

BY THE TIME I walked into the salesroom that morning, my own interest in this perplexing figure had already blossomed into a consuming curiosity. It had begun three years earlier, in the manner of so many memorable adventures: with an unintended detour.

In February of 2001, as part of the promotional effort for my earlier book, The Island of Lost Maps: A True Story of Cartographic Crime, I found myself in Jacksonville, Florida, at a literary festival affiliated with the city’s public library. My first morning in town had been spent doing lectures before classes of half-awake high school students, and by the time it was over I was jet-lagged and ready to head back to the hotel.

Mark Allen had other ideas. An affable retiree who was donating his time to the festival, Mark was assigned to get me where I needed to go that weekend. We had struck up a quick rapport. He had lived an interesting life and, better yet, knew how to make good stories of it. Earlier that day, he nonchalantly flipped a street atlas into my hands, said, “Here, you’re the map guy,” and appointed me navigator. Then he launched into some marvelous yarn about his youthful adventures in the Philippines, causing me to forget my duties. An exit was missed; the Map Guy was teased. Now Mark had more fun on his mind.

“I’ve got one last stop for you,” he cheerily announced. “How would you like to swing by the Fort Caroline National Memorial?”

I left the question unanswered. The temperature had been in the 20s when I left Chicago. In Jacksonville, it was more than 80 degrees. The hotel pool was big and wet. I had never heard of the Fort Caroline National Memorial.

“Trust me,” he said. “This place will interest you.”

So we took a drive. Heading east through downtown Jacksonville, Mark began to tell another engrossing story—this one about a group of Frenchmen who in 1564 attempted to establish the first permanent European colony in what is now the United States. That tale had a familiar ring to it, and by the time we pulled into the parking lot, shadowed by live oaks draped in Spanish moss, I knew why.

Before getting out of the car, I flipped open my battered copy of The Island of Lost Maps. The artwork selected for the book’s dust jacket and endpapers was a cartographic treasure from 1591 called Floridae Americae Provinciae Recens & Exactissima Descriptio. It lay in front of me now. The map showed Florida as a vast region, covering all of the modern-day southeastern United States. This sprawling area was, in the sixteenth century, contested by Spain, England, and France, and the story of how these three powers battled for primacy there was one of the most gripping and bloody chapters in early American history. The map itself was intended, in fact, to bolster France’s claim to sovereignty, as evidenced by the royal coat of arms that occupied hundreds of square miles of Terra Florida.

Sitting there, I realized that the man who drafted this map more than four hundred years ago had resided not far from this very spot, somewhere around the bend from those upscale homes and shopping plazas we had just passed. I did not know then that Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues had barely escaped this place with his life, or that scores of his compatriots had been slaughtered near here, or that after the bloodbath he had somehow managed to make his way back to Europe in an ill-manned ship with nothing to eat but biscuits and water. I was, moreover, completely ignorant of Le Moyne’s lives away from this place: as an important early botanical painter, for instance, or as an employee of Sir Walter Raleigh.

I had always had a special fondness for Le Moyne’s map and its many curiosities: the toad-faced sea monster, the triangular shape of the Florida peninsula, the massive inland sea on the uppermost border, the Atlantic coastline that keeps veering east where it should turn north. One commentator had politely described the work as “curiously inexact” another had less charitably declared it to be “compiled from a series of disjunct sketches drawn on different scales, or with no scale.” It was a handsome map, a fascinating map, even an important map—just not a good map. Le Moyne was, at best, a run-of-the-mill cartographer. His contributions in another area of New World discovery, however, were entirely unique.

Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues was the first European artist in North America. Until he arrived near where I was now standing, the only images of native people and landscapes had been done by amateur adventurers or by draftsmen working with imported models or secondhand information in the safety of their European studios. Le Moyne was the first professional artist known to have visited what is now the continental United States with the express purpose of making a visual record.

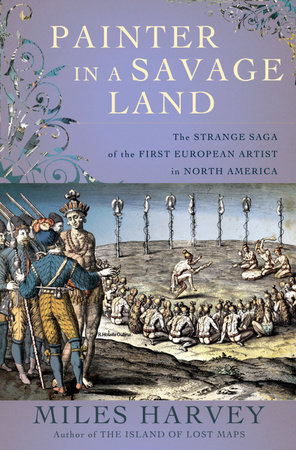

In the course of my research for The Island of Lost Maps, I had come across his vivid and sometimes gruesome depictions of native life, made famous in a series of engravings. Full of tattooed Indians wearing clothes made of birds’ heads and inflated fish bladders and moss and practicing rituals that involved fruit-stuffed deerskins or severed human limbs impaled on long sticks, those images had always struck me as profoundly unfamiliar, not so much from another century as from another world entirely. But now, as I wandered around this exotic landscape, perfumed with lush subtropical smells, I began to feel that distant place pulling me in.

The Fort Caroline National Memorial is part of the forty-six-thousand-acre Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve, the setting for one of the last unspoiled coastal wetlands on the Atlantic coast. The memorial itself, however, is a modest place, more notable for what is missing than for what remains. At the visitors’ center, Mark and I saw a wooden canoe made by the Timucua, the dominant Native American group in the region at the time of European contact. These people, I learned, had vanished centuries ago. We then visited a two-thirds-scale replica of the fort, modeled in part after an illustration attributed to Le Moyne. The original fort, it turned out, had also disappeared, leaving few clues about its exact location. In truth, there was not much to see: almost no trace of the people and places Le Moyne painted has survived. Yet perhaps those absences stirred my imagination, for later that day, as I sat in the pool after parting company with Mark, I could not stop wondering about the fort and the artist who had called it home.

Over the next several months, I began prowling libraries to find out more about Le Moyne. It was not easy work. Like so many other things associated with Fort Caroline, much of his life story had disappeared. Thirty years were missing from his biography before he came to the New World, and there was another gap of fifteen after he returned to France. And although Le Moyne produced an extraordinary body of work, both written and pictorial, about his experiences in Florida, we know it only secondhand. He left a riveting narrative of his adventures in the New World, but the original manuscript of that work, written in French, has long since disappeared, leaving only Latin and German translations of questionable accuracy. Of all his paintings of Native Americans, meanwhile, only one original has ever been thought to survive, and even its authenticity is highly questionable. The remaining images come to us from a series of prints based on his vanished artwork and published by the Flemish engraver Theodor de Bry after Le Moyne’s death. De Bry, however, is known to have liberally embellished, restructured, and recrafted the artist’s work. It’s often unclear where Le Moyne’s hand leaves off and de Bry’s begins.