Excerpt

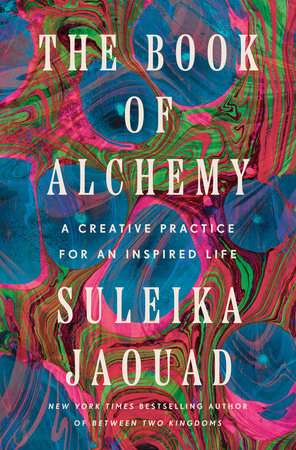

The Book of Alchemy

Chapter 1On BeginningNot long ago, I was invited to a conference billed as a gathering of fifty of the world’s most innovative thinkers. Each day, there were lectures by everyone from leading scientists and tech CEOs to pioneering artists and actors and Arctic explorers. Afterward, we’d meet up in breakout sessions to discuss and debate the implications of their ideas. In these smaller groups, people would often start the conversation by identifying their field, then asking, “And what do you do?”

It’s that oh-so-human need to categorize, to sort by type, but as a writer, I’ve come to dread answering the question. I know the follow-up will be: “What kind of writing?” Much of my work has lived in the realm of memoir, which is often characterized (unfairly, I believe) as navel-gazing and lacking rigor, especially when the author is a young woman. In certain company, I sometimes feel tempted to beef it up, to make it sound more “serious.” Rather than saying, “I wrote a column about being a young adult with cancer,” I find myself wanting to say, “I used to write for the New York Times science section.”

So imagine my inner panic when, in the middle of this group of intellectuals, business scions, and Nobel-winning scientists, I was asked, “A writer, huh? So what is it you’re working on now?”

I was working on this book—this distillation of a practice that has saved my life. “A book about journaling,” I replied. I watched the answer fall flat, just as I’d feared. In that knee-jerk way, I felt I needed to justify it. To explain that, though journaling is sometimes dismissed as a childish pastime you do in a pretty diary with a tiny lock, its physical and mental benefits have been extolled in study after study—everything from reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety to improving working memory and strengthening the immune system. “It’s something everyone could benefit from,” I wanted to shout, “maybe especially you!”

I didn’t say that. Instead, I quickly changed the subject back to them and their pursuits. I have always thought of journaling as serious—it has had very serious applications in my life—but I’ve never been very good at the one-sentence pitch. If I could go back and explain why I feel called to share my particular approach to journaling, I would say this: I do this work because I know it works—and it’s necessary. The studies may be useful to sway the skeptics, but they’re just confirmation of what I already know on a soul level.

This is not just true in my own life. I have heard from more people than I can count testifying to how transformative this practice has been. A fifty-year-old woman who was stuck in a soul-sucking corporate job used these tools to realize her lifelong dream of becoming a writer: Her journal entries turned into prize-winning essays; she wrote a memoir, got an agent, and quit her day job. A mother reeling from the loss of her daughter began making art from these prompts, which allowed her to feel connected to her daughter and begin to process her grief. An oncologist who saw the health benefits of this approach to journaling has literally prescribed these prompts to over a hundred patients. I could fill pages and pages with stories like these.

Journaling as a process is utterly alchemizing, with practical applications in every area of one’s life and work. The journal is like a chrysalis: the container of your goopiest, most unformed self. It’s a rare space, in this age of hypercurated personas, where you can share your most unedited thoughts, where you can sort through the raw material of your life. Day by day, page by page, you uncover the answers that are already inside of you, and you begin to transform. And yet, at the same time that it offers transcendence, there’s nothing more humble than the journal. As long as there has been literacy, people have turned to it to catalog the everyday, which the word’s etymology makes clear. It comes from the Old French word jurnal, which has its roots in the Latin diurnalis, meaning “of a day.” If you trace the origin of the word diary, it’s the same. The oldest journals we know of were for recordkeeping, like the Diary of Merer, the ancient Egyptian papyrus logbook that recorded the transport of limestone to Giza, where it was used as cladding for pyramids.

Over the years, the form evolved from simple cataloging to include much more: everything from Marcus Aurelius’s private musings turned guide to life, Meditations; to the “pillow books” of the women of the Japanese court around A.D. 1000 (so named because they hid the diaries beneath their pillows), which detailed their public lives as well as fantasies and fictional tales; to the scientific notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci and Charles Darwin.

In the twentieth century, we get Anaïs Nin’s most intimate thoughts about her sexual and political awakenings and Virginia Woolf journaling about her reading and writing life. We get the diaries of individuals grappling with their private lives against the backdrop of repressive regimes, like Alice Dunbar-Nelson, who gives us an unadulterated look into the life of an early-twentieth-century woman of color in America, and Anne Frank, who famously documented her experience as a young Jewish girl in hiding under Nazi persecution.

Journals have become important historical artifacts, giving us glimpses into the past and providing insight into what our fellow humans lived through, be it illness or war or some other crisis, and how they managed to endure. As Anaïs Nin wrote, “When we go deeply into the personal, we go beyond the personal. We achieve something that is collective.”

The journal is capacious. It can be an aid to memory, a reliquary of major life events, a place to let off steam, rattle off lists of dos, don’ts, and dreams, or conjure something beautiful and wild and unexpected. It’s where we can go to cut through the noise, where we take stock and discover meaning, where we tap into the subconscious and our free-flowing stream of intuition. The journal is where we seek out and find our highest, most liberated, most creative self.

But whether you’re a longtime journaler or new to the practice, you’ve likely experienced that moment when you behold the blank page and are stricken with the question: How do I begin?

For me, it starts with the journal itself. Whether it’s a classic composition notebook from the drugstore or a leather-bound beauty, I always personalize it in some way. I adorn the cover or write myself a creative contract on the flyleaf or tuck a favorite old photograph into the opening pages—anything that amplifies its appeal and encourages me to return. I also keep handy a stock of my favorite pens.

The physical, tactile nature of journaling by hand is important to me. I love the interaction between paper and palm, how the pen glides across the page, how the letters emerge as images—swooping up, looping back, charging forward. “There is a state of mind which is not accessible by thinking,” writes Lynda Barry in her creative workbook and graphic memoir, What It Is. “It seems to require a participation with something, something physical we move, like a pen, like a pencil, something which is in motion—ordinary motion, like writing the alphabet.” Virginia Woolf also extols the joy of writing by hand; after spending many months revising a manuscript on her typewriter, she returned to pen and paper, and in her journal, she wrote: “How I should like . . . to write a sentence again! How delightful to feel it form and curve under my fingers.”

If you’re feeling resistant to the idea of writing by hand, what I’ll say is this: I myself find it useful, both because I like the unfurling of ink on the page and also because I’m less likely to self-edit that way. But we all have different needs, and you should feel free to journal in any way that makes sense for you—be it on a laptop, on your phone, or on a legal pad with a pencil stub.

Often, when I get to the page, several self-sabotaging thoughts rear their heads: “I have nothing to say” and “I don’t feel inspired to write one word, much less fill three pages” and “I’m never going to be able to do this consistently, so what’s the point?” I’ve concocted a number of tricks for pulling my mind out of those ruts, but one of my favorites was shared with me by the poet Marie Howe: “Whenever I can’t do the practice, I’ll get a composition book, and I’ll write three pages a day, but I write it with my nondominant hand, so it’s a big scrawl,” she said. “Or I’ll write, ‘I don’t want to write about . . .” and then just write into that—so there’s a release in it.”