Excerpt

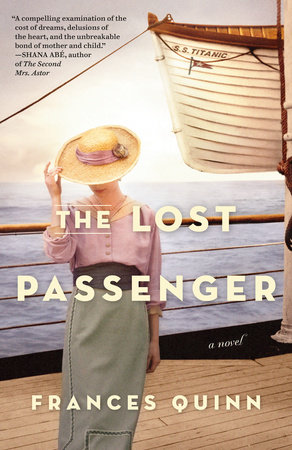

The Lost Passenger

Chapter 1 If I shut my eyes, I can still picture the invitation that started it all. Thick, cream-colored card, embossed with black copperplate.

Lord and Lady Burnham request the pleasure of your company for a New Year’s ball at Chilverton Hall, 12th January 1910

I’d been with my father at Star Mill all afternoon, arguing up hill and down dale with him over dye samples for our spring prints. I won the fight for sapphire blue and a beautiful emerald green—the ladies’ magazines were going mad about jewel colors—and while he made out the order, I sorted through the post. Mostly invoices, but then this very swish cream envelope.

His eyebrows shot up as he read the words. Our house, Clereston, wasn’t far from Lord and Lady Burnham’s estate, but we didn’t move in those circles at all.

“Why the heck would they invite us?” He held the card over the wastepaper basket, his eyes twinkling. “We’ll say no, won’t we?”

He knew perfectly well that I’d be for going. I’d been taken with the idea of going to a ball since my mam told me the story of Cinderella, when I was a little girl, and just lately I’d read all Jane Austen’s novels—even

Lady Susan, which hardly anyone likes—and they’re full of them. Of course we’d go.

As we walked in that evening, both a bit nervous though we’d not admitted it, he said, “Think how proud your mam would be.”

He was wishing she was with us, and I was too, but then there’d barely been a day in the past five years when I hadn’t thought of her and missed her, and him the same. And she’d have loved it, my mam: women in satin and silk, jewels glittering under the chandeliers; men in tailcoats with snow-white waistcoats and ties; a violin quartet playing; and this lovely hum of conversation and laughter over it all. Everything I’d imagined.

Lady Burnham greeted us, very friendly, and promised to introduce us to “some delightful people” once everyone had arrived. After we’d stood and watched the dancing for a while, my father went to refill our glasses and she led him over to the far side of the room, where he was soon caught up in conversation. I had

Pride and Prejudice and Elizabeth Bennet’s humiliation at the Meryton ball fresh in my mind, so I wasn’t going to stand about looking desperate for someone to ask me up. I’d tucked myself a bit behind a pillar when a lanky young man, a few years older than me, walked by. He stepped back, and smiled.

“Are you hiding? Wouldn’t blame you, there are some dreadful people here.”

I was flattered he didn’t lump me in with the dreadful people, and that smile, easy and open, made me like him straight away. Doing my best to sound as though I went to balls every night of the week, I said, “Just waiting for my father to stop chatting and bring me a glass of champagne.” And then, because he had kind eyes. “But I am hiding, a bit. I don’t know anyone here.”

“We must remedy that.” He put out his hand. “Frederick Coombes.”

“I’m Elinor Hayward.”

“There, now we know each other. I’d ask for a dance, but I’m a little incapacitated.” He tapped his leg. “Riding accident, sprained my ankle.”

“That sounds painful. Did you fall off?”

“Rather spectacularly. But it’ll mend, and it gives me a good excuse to stay here and talk to you.”

When my father came back, I introduced them.

“Of course! Hayward! I should have realized,” said Frederick. “You’re the cotton king.”

My father rolled his eyes. “Just a daft thing the papers say.”

He loved it really. They all called him that, and they liked to tell his story. How he’d started out working in a little drapers’ shop in Manchester, realized he could run it better than the owner, scrimped and saved to buy it, and built the rest from there: the mills and the printworks, two more shops, and hundreds of people working for him.

“Very impressive,” said Frederick, “what you’ve done with your business. Didn’t I read you’ve electrified one of your mills completely?”

“Star Mill,” said my father. “You read about that?”

“I did. Very interesting.”

I checked his face for signs of sarcasm, because not everyone found the cotton trade as fascinating as we did. But he seemed properly interested, even asking quite a sensible question about how we’d switched from steam to electricity. I liked him all the more then, because I was proud of my father’s achievements, and our business.

Even so, when a bell rang for supper, I expected he’d make his excuses. My father was talking about his new looms by then, and my mam always said that if you let him near the subject of machinery, you’d get the ins and outs of a pig’s backside, no detail spared. But Frederick said, “I wonder, Mr. Hayward, may I introduce you to my mother? My father was unable to attend this evening, so it falls to me to take her in to supper, and I was hoping you might allow me to escort Miss Hayward.”

My father looked as surprised as I felt, but he said yes. (It was only much, much later that it struck me: neither of them asked me.) We followed him over to the other side of the room.

“Miss Hayward, Mr. Hayward . . . my mother, Lady Storton.”

Lady? I wasn’t expecting that, and my father’s intake of breath said he wasn’t either.

She was frighteningly elegant, slender on the verge of bony. The dress was very good silk—my father was pricing it with his eyes—and diamonds glittered at her throat. I’d a diamond necklace on too, but mine was bought that week, and I kept checking it was still there. Hers had the look of a family heirloom and she wore it as though she hardly knew she had it on.

Lady Storton smiled. “I see my son has found better company than mine. May I prevail on you to take me in, Mr. Hayward?”

My father copied the way Frederick held out his arm to me, and we strolled in to supper, the cotton king and the cotton king’s daughter, with the wife and son of an earl.

It was stupidly easy to fall in love with Frederick; I got halfway there that very evening. But I’d like to point out, before you decide I must’ve been soft in the head, that I was nineteen, he was the first man ever to pay attention to me, and he was very, very charming.

As Lady Storton swept my father away, he waited on me as if I were a princess, fetching me a glass of champagne, then dashing off and coming back with a plate of chicken in a creamy sauce speckled with herbs.

“Lady Burnham’s cook is famous for her fricassée. I had to distract the Duchess of Bolton to snaffle this portion.”

“How did you do that?”

“Told her the Prince of Wales had made a surprise appearance. She’ll never speak to me again when she finds out he hasn’t, so I hope you wouldn’t have preferred the roast beef.”

I’d read that a lady never finishes everything on her plate, but it was quite a small portion.

“I should probably warn you,” I said, “that I’m hungry and I might have to embarrass you by eating the lot.”

He grinned. “Eat away. We’ll be pariahs together.”

I’d never been flirted with before, but when you’ve read as many novels as I had, you know what it looks like. What I didn’t know was how it makes you feel, when a personable young man ignores everyone else in the room to talk to you, and looks into your eyes as though he’s never seen eyes before, and every so often brushes your hand with his, as though by accident but definitely not. And all the while, we chatted like old friends, finding we had all sorts in common. Neither of us thought much of the latest Mary Pickford film; both of us were intrigued by the rumors of a fresh attempt on the South Pole. We’d both read about the new ship being built in Belfast, the biggest ever, with restaurants and squash courts and a swimming pool, and when I said my father planned to book us on its maiden voyage, Frederick was envious.

“How marvelous. I’d love an adventure like that!”

We’d ordered our car for midnight—late for my father, who liked to be up and getting on with the day before most people had even had breakfast—so all too soon, it was time to go.

Dropping a kiss on my hand that made me blush, Frederick said, “This won’t, I hope, be goodbye. I’m staying here at Chilverton a while. Might I call on you both before I go back to Kent?”

Everyone knows what it means when a single man asks to call on a household with an unmarried daughter in it. Even my father, who normally paid very little attention to anything that didn’t involve cotton.

“Well,” he said in the car, “I wasn’t expecting this.” He drew himself up and said in a plummy voice, “Lady Elinor, pleased to make your acquaintance.”

“Stop it!”

“Any fool could see he likes you. But do you like him? If not, earl or no earl, we’ll call a halt to it.”