Excerpt

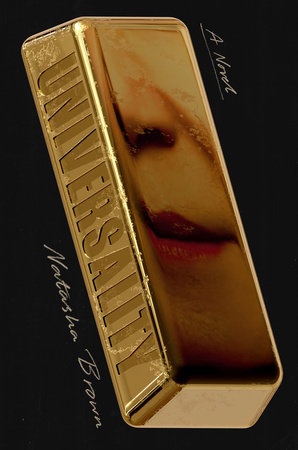

Universality

A Fool’s GoldFirst published in

Alazon magazine June 17, 2021

A gold bar is deceptively heavy. Four hundred troy ounces, about 12.5 kilograms, of ultra-high-purity gold formed into an ingot—a sort of slender brick crossed with a pyramid. Holding one such bar on a chilly September evening last year, thirty-year-old Jake marveled at its density; how the unyielding sides and edges felt awkward, yet somehow natural, in his hands. Behind him, from the main building of a West Yorkshire farm, music and colored lights throbbed against the night sky. Roughly one hundred youngsters were partying in defiance of the British government’s lockdown restrictions. Jake didn’t look back toward the noise pumping from the farmhouse where he’d spent most of his fraught 2020. He wasn’t even looking at the gold, not really.

The bar in Jake’s possession was a London Good Delivery—literally the gold standard of gold bullion—worth over half a million dollars. An obscene concept; Jake couldn’t quite believe it was possible to hold so much “value” within his two hands. Let alone to wield it. Again and again. Again. Until his target had finally stopped moving. But it had happened, hadn’t it? Yes, it had happened. He couldn’t stop himself from staring at the proof. The motionless body lying at his feet.

At some point that night, or perhaps as daylight crept in at the edge of the horizon, Jake managed to stop looking and start thinking.

He decided to run.

In the weeks following Jake’s disappearance, the Queensbury and Bradford local papers reported on the events of that night: an illegal rave, the resulting three hospitalizations, significant property damage, and an ongoing police investigation. The story was soon forgotten, however, as national focus remained on the pandemic and the government’s strategy heading into the challenging winter months. Yet unraveling the events leading to this strange and unsettling night is well worth the trouble; a modern parable lies beneath, exposing the fraying fabric of British society, worn thin by late capitalism’s relentless abrasion. The missing gold bar is a connecting node—between an amoral banker, an iconoclastic columnist, and a radical anarchist movement.

“Of course I want it back—it’s my gold.”

Richard Spencer has not forgotten the events of that night. Indeed, as the legal owner of the farm, he thinks of little else. “I want my life back,” he complains miserably. The first time I meet Spencer, he sits across from me, his elbows propped against the dull aluminum top of our outdoor dining table. He chose the place—an earnestly ironic American-style diner in London’s Covent Garden. The menu lists an £11.50 avo ’n cream cheese bagel. Spencer wears a deep-blue Ted Baker shirt, starchy but unironed, with the sleeves rolled to mid-forearm, lending a disembodied, theatrical effect to his expressive hands and wrists. He’s garrulous, keen to detail the many ways his life has been turned into “an absolute shit show.”

An overly indulgent, even selfish, comment, perhaps. After all, since the pandemic swept across the globe in 2020, many people have suffered badly, losing their lives and loved ones. Spencer is alive and well. His loved ones are safe—though possibly not reciprocally loving at this moment. But Spencer has lost something significant: his status. Back in 2019, all the excessive fruits of late capitalism were his. He owned multiple homes, farming land, investments, and cars; he had a household staff; a pretty wife, plus a much younger girlfriend. As a high-powered stockbroker at a major investment bank, he enjoyed immense power, influence, and wealth. He had everything. Now, stripped of all that, he has become the man across from me: a grounded giant, cut off from his castle in the sky.

Spencer’s gold-thieving, beanstalk-chopping “Jack” is Jake from the farm, whom he suspects of having run off with the gold. “Of course he bloody took it with him,” Spencer says, certain of his own version of events, despite having never met Jake.

In fact, Spencer knows virtually nothing about the man he blames for his ruin. Spencer invited Jake to the farm as “a favor to Lenny,” a woman he’d met in his building. “Her friend needed a place to quarantine for a few days,” he says simply. Spencer doesn’t know much about Lenny, either. She was one of the few who remained in their Kensington apartment block during the lockdown, a time when most residents retreated to secondary homes. Does he know her surname? “No.” Age? “Um, mature.” Her flat number? “I couldn’t say for certain.” What did he actually know about this woman when he decided to hand her the keys to his farm? “Well . . .” He hesitates. “I knew her pretty well, in a sense . . .”

Reluctantly, Spencer will admit to his philandering. He is separated from his wife, Claire, who remains in the family home raising their three-year-old daughter, Rosie, alone. “Not exactly alone,” he’s keen to point out. “They have the nanny four days a week. And it’s not like Claire has a job.” Claire and Spencer split in 2019 over his tryst with a colleague fifteen years his junior.

“Typical. He would say that.” Claire opens the large front door to her Cobham home one-handed when I stop by days later. A shyly curious toddler clings to her left arm. We sit down at the kitchen table with a pot of filter coffee between us. Little Rosie lies on the soft-play mat in the corner kitted out in stripy leggings, a builder’s hard hat, and a glittery tutu, mumbling as she forces plastic trucks to collide. “I’m a designer,” Claire says. Since Rosie’s birth in 2018, Claire has taken on part-time freelance work for a handful of clients. Before that, she worked at a boutique branding agency, after studying art history at Oxford, where she met Spencer. The pair married soon after graduation, spending a few years in London before moving to this exclusive village, favored by footballers and financiers, and starting a family.

Claire is sanguine about their separation. “People change, don’t they?” Their house in Cobham never really felt like Spencer’s home. “He stayed in the city mostly. His hours were so long it made sense.” In recent years, Spencer had begun spending weekends at his Kensington pied-à-terre, too. “I’m not stupid,” Claire says of the affairs. “I know what goes on.” Still, it wasn’t until Claire discovered the extent of Spencer’s involvement with a younger colleague that she decided to officially call it quits. “There’s a line,” she says. Spencer had crossed it.

In 2015, Spencer’s father died after a prolonged illness. “That was the beginning of his farm obsession,” according to Claire. Every weekend, Spencer would attend auctions or travel to remote towns to view land plots and properties. A late effort, perhaps triggered by grief, to emulate his father—a “man’s man” who built a successful construction company from the ground up. “His dad never quite understood him,” Claire says. “But Rich idolized the guy.” Eventually, Spencer bought Alderton, an old hill-top farm in Queensbury, a quiet West Yorkshire village. Claire didn’t think much of the property. “It was a complete wreck. A rubbish heap on a big hill in an awful little town. No one with any sense would touch it.”