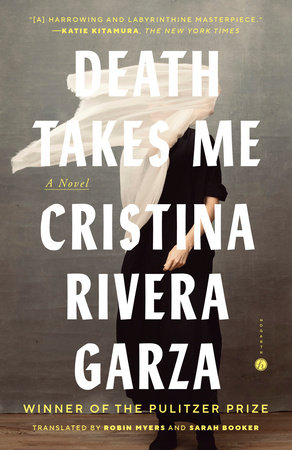

Excerpt

Death Takes Me

1What I Believed I Said“That’s a body,” I muttered to no one or to someone inside me or to nothing. I didn’t recognize the words at first. I said something. And what I said or believed I said was for no one or for nothing or it was for me, listening to myself from afar, from that deep inner place the air or light never reaches; where, hostile and greedy, the murmur began, the rushed, voiceless breath. A passageway. A forest. I said it after the alarm, after the disbelief. I said it when my eye was able to rest. After the long spell it took for me to give it form (something visible) (something utterable). I didn’t say it: it came out of my mouth. The low voice. The tone of terror. Or of intimacy.

“Yes, it’s a body,” I had to say, and instantly closed my eyes. Then, almost immediately, I opened them again. I had to say it. I don’t know why. What for. But I looked up and, since I was exposed, I fell. Seldom the knees. My knees yielded to the weight of my body, and the vapor of my faltering breath clouded my vision. Trembling. Leaves tremble, and bodies. Seldom the thundering of bones. Crick. On the pavement, to one side of the pool of blood, there. Crack. The folded legs, his insteps face-up, the palms of his hands. The pavement is made up of tiny rocks.

“It’s a body,” I said or had to say, barely stammered, to no one or to me, who could not believe it, who refused to believe me, who never believed. Eyes open, disproportionately. The wail. Seldom the wail. That invocation. That crude prayer. I was studying it. There was no way out or cure for it. There was nothing inside and, around me, there was just a body. What I believed I said. A collection of impossible angles. A skin, the skin. Something on the asphalt. Knee. Shoulder. Nose. Something broken. Something dislocated. Ear. Foot. Sex. An open, red thing. A context. A boiling point. Something undone.

“A body,” I believed I said or barely muttered for no one or for me who was becoming a forest or passageway, an entrance orifice. Blackness. I believed I said. Seldom the lips that refuse to close. The shame. His final minute. His final image. His final complete sentence. The nostalgia for it all. Seldom. Staying still.

When I said again what I believed I said, when I said it to myself, the only person listening to me from that far-off inner place where air and light are generated and consumed, it was already too late: I had made the necessary calls, and because I was the one who had found him, I had already become the Informant.

2My First BodyNo, I didn’t know him.

No, I’ve never seen anything like it.

No.

It’s difficult to explain what you do. It’s difficult to tell someone as they interrogate you with a brown, vehement, crepuscular gaze that it’s better, or at least more interesting, to run through alleys than on the city streets. Is a city a cemetery? That it’s even better to run there than on a track. A blue place. Something that isn’t a lake. The knees are the problem, clearly. And the danger. It’s difficult to confess to an official from the Department of Homicide Investigation that danger is, precisely, the allure. That the allure is the unexpected. Something different. It is difficult to detail, in all its slow dispersion, your daily routine, so that someone interested in something else, someone interested in solving a crime, will understand that running through the alleys of the city is a better alternative to running on tracks or on illuminated sidewalks: that is a difficult thing. To tell her: that’s really it, officer, the danger: what’s hiding there: what doesn’t happen elsewhere. It’s difficult to speak in monosyllables.

I was running. I usually run at dusk. Also at dawn, but usually at dusk. I run on the track. I run from the coffee shop to my apartment. I avoid sidewalks and roads; I prefer shortcuts. Alleys. Narrow streets. No, I don’t run for exercise. I run for pleasure. To get somewhere. I run, if you will, utilitarianly.

There’s no time to say it. It wouldn’t interest her. But running, this is what I think, is a mental thing. In every runner there should be a mind that runs. The goal is pleasure. The mind’s challenge consists of staying in place: of the breathing, of the panting, of the knee, of the hand, of the sweat. If it goes elsewhere, it loses. If it wanders off, it loses even more. The mind’s challenge is to be the body. If it aspires to it, if it achieves it, the mind then becomes the accomplice, and there, from that complicity, the detour that moves the mind and body away from boredom emerges. The detour is the pleasure. The goal.

Yes, sometimes there are dead cats. Pigeons. No, never men. Never women. No, none of that. This is my first body.

It’s difficult to speak to you informally. Why would that be?

To see you: well-groomed, white shirt, patent leather shoes. We know that everything is a cemetery. An apparition is always an apparition. You tell me nothing changes. Why shouldn’t that be questioned? I’m sure you know how to whistle. You have that kind of mouth over the half-open mouth that neither air nor night comes through. My first.

Sometimes junkies. They share needles. They offer them. Yes.

No. I just run. That’s all.

The endorphins, they explain to me, cause addiction. You start to run and then you can’t stop. If that counts, then yes. Addict.

First there’s the sensation of reality that prompts the falling onto your own two feet. Once. Again. Once and again. Measured, the trot. The steps. It’s possible that someone runs away, frenzied. That intermittent relationship between the ground and the body—the weight of the two. Gravity and anti-gravity. A dialogue. A burning discussion. And the relationship, also intermittent, between the landscape and the mind. The silhouettes of the trees and the flow of the blood. Everything happens so quickly at the end, that’s what they say. The colors of the cars and the more recent concern. The angles of the windows and the memory or the pain. An entire life: the words: an entire life. The struggle, always ferocious, to concentrate. I am here. I am now. That’s called I Am My Breath. The internal sound. The rhythm. The weight. The scandalous murmur of the I within the dark fishbowl of the skeleton. But it’s still so difficult to speak to you informally. Only later the loud noise. The ardor. The air that seems to thin out in the nasal cavities: narrow ridges in the lungs. An implosion. That violent unleashing of the endorphins, producing a euphoria that in many ways resembles desire or love or pleasure. What will come of all this, my First? The lightness. The speed. The possibility of levitating. When I start running, that’s the moment I’m searching for. That’s the moment I pursue. That’s the goal.

Yes, I write. Also. Also for pleasure, like running. To get somewhere. Utilitarianly. To get to the end of the page, I mean. Not for exercise. If you know what I mean: it’s life or death.

It’s difficult to explain what you do. The reasons. The consequences. The processes. It’s difficult to explain what you do without uncontrollably bursting into laughter or tears. My eye is looking at me now, unguarded. Before the image of the murdered body that inserts itself like white noise into the interrogation; before what we no longer see but can’t stop seeing, what the hell does it matter if we get to the end of the page or not? It’s a rectangle, don’t you see? I ask her. I’m not in any shape to say that doing this, getting to the end of the page, is a matter of life, a matter of death. Where’s the blood to prove it? you ask me. Where’s my blood? You nod, perplexed.

No, I’d never seen him in the neighborhood.

Yes, I do generally pay attention to those things. New faces. Lost pets. Businesses. Yes, personal, social interactions. But I hadn’t seen him around here. No.

I’m sure.

Yes, I’m aware that he was missing a penis. Mutilation. Theft. The lack. I’m aware of all this.

Yes, it’s a terrible thing against the dead.

I can’t anymore.

I’m sure.

A terrible thing. Yes. Against the dead.