Excerpt

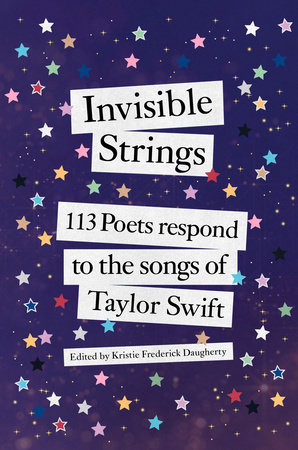

Invisible Strings

IntroductionKristie Frederick Daugherty

I am a debut-era Swiftie—I remember the first time I heard Taylor Swift’s young voice singing “Teardrops on My Guitar” from my daughter’s CD player. I have attended many of Swift’s concerts, from her first headlining tour, Fearless, all the way through to her Nashville and Cincinnati stops of the Eras tour.

At the kickoff stop of the Fearless tour in Evansville, Indiana, I was sitting with my daughter at the end of an aisle, and at one point Swift brushed my arm as she made her way back to the stage after starting a song at the top of the stadium. While I knew then that Swift’s lyrics had staying power, I had no idea that Swift would become a singer whose words would move hundreds of millions of fans across the globe. And I certainly had no idea that her lyrics and the art form in which I write—poetry—would one day intersect to take the shape of this anthology. I like to think of the slight brush of Swift as she walked past me in Roberts Stadium on April 23, 2009, as foreshadowing of this anthology. It is pretty to think so.

In addition to being a Swiftie, I am also an ardent reader and writer of contemporary poetry. And I know—as Sir Jonathan Bate discusses in the foreword—how well Swift has trained her fans in the art of close reading. I’ll never forget the magic of sitting up high with my friend Leslie Wilhelmus on the second night of the Cincinnati Eras tour at Paycor Stadium, as sixty-five thousand Swifties sang along to every single word of a forty-four-song set. Swifties also recognize the literary devices of poetry weaving through Swift’s rich discography. Swift has taught her fans to read her lyrics carefully, attending to syntax, symbol, and sound, just as poets learn to read literature. Swifties spend countless hours discussing Swift’s songs with one another, on social media, and even in the increasingly common Taylor Swift classes—Stephanie Burt’s Harvard course “Taylor Swift and Her World” is just one example.

Swifties have a love language, and I am fluent.

So, as I watched as Taylor Swift announced her new album,

The Tortured Poets Department, during the Grammys, a question popped into my mind: How might contemporary poetry grab this moment? Could poetry and poets join in conversation with Swift? As quickly as the question formed, so did an answer: an anthology in which poets would respond to Taylor Swift’s songs without quoting her lyrics. That way fans could, to quote Shakespeare, “by indirections find directions out” by close reading the poems to discover the songs behind them.

I immediately messaged the Pulitzer Prize–winning poet Diane Seuss. Like Swift, Seuss is a woman who must be protected at all costs, a woman who says the words for us. I asked Seuss if she would contribute a poem to this anthology, then watched as those three dots on

Messenger appeared and disappeared. A “yes” from Seuss would decide if the anthology could take off. Her message appeared: “Yes. And here is a list of people to invite. You may tell them I am contributing.”

Often in my life, Diane Seuss has been there for me, her latest volume of poetry tucked into my purse just to keep her words near. And in 2022, when I messaged Seuss directly for the first time to express my love for her poetry, she messaged right back. We spoke for more than an hour—and she generously shared her poetic wisdom.

Swift has been there for me too, all along, in her own way—with every new album illustrating growth as a lyricist. After folklore and evermore, I did not know how Swift could possibly write another album at a higher level. But that manner of thinking does not work with Swift because her albums simply aren’t comparable. Swift doesn’t just make another album; she reinvents; she deconstructs to construct.

The Tortured Poets Department shows us a songwriter in full control of her powers, one who mixes metaphors and doesn’t care. Swift embodies the famous lines by Hélène Cixous from “The Laugh of the Medusa”:

Because she arrives, vibrant, over and over again; we are at the beginning of a new history, or rather a process of becoming in which several histories intersect with one another. As a subject for history, woman always occurs simultaneously in several places.

Swift does arrive, vibrant, over and over again, dropping lines like, “Did you hear my covert narcissism / I disguise like altruism / like some kind of congressman” in a pop song, and everyone sings along while googling for definitions—it’s a real thing, how Swift increases the lexicon of her fans. She also moves brilliantly within and between the songs on her albums. Her songs talk to one another, reshape themselves, and get recontextualized as Swift reinvents herself. “Hits Different,” the last track on

Midnights (The

Til Dawn Edition), ends with, “Have they come to take me away?” Meanwhile,

The Tortured Poets Department begins with the song “Fortnight” and the line “I was supposed to be sent away / But they forgot to come and get me.” And just like that, Swift transforms the space between

Midnights and

The Tortured Poets Department from silence to an audible pause, as if continuing a life libretto.

There is always a link.

This is the magic of Taylor Swift—a magic she cultivates in her fan base. Everything connects. The center does not fall apart—it orbits itself to create a new thing. Younger listeners find themselves in her earlier albums—but Swift also brings new meaning to earlier work through, for example, the “Five Stages of Grief” playlists on Apple Music and the acoustic set song mash-ups on the Eras tour. When she placed the song “Lover” on her “denial” playlist (called “I Love You, It’s Ruining My Life”), fans took to social media in shock and disbelief, wondering if it was still “okay” to have played “Lover” at their weddings. Of course it was, but that is the genius of Swift: She’s not afraid to recontextualize. She welcomes it: She has trained her fans to follow her threads. She can teach millions of people to synthesize, to analyze, to think critically. That’s the genius of Dr. Taylor Alison Swift.

The poets here give evidence for that genius. The 113 gathered here include six Pulitzer Prize winners, many Pulitzer finalists, emerging poets, Instapoets, and

New York Times bestselling poets. As I sent out invitations, I kept this Swift quote close: “The worst kind of person is someone who makes someone feel bad, dumb or stupid for being excited about something.” Emboldened by Swift’s words, I let my enthusiasm be on full display as I corresponded with the poets. I was, and remain, the awestruck, poetry-loving, Swiftie fangirl. And the poets responded in kind, with joy, curiosity, and a willingness to play.

That play became this book’s magic, and my own. I deeply love contemporary poetry and Taylor Swift, and this anthology combines my loves. It contains words by poets whose words have shaped me, written in direct response to the singer whose own words have, time and again, shored me up and brought me back to myself. “All Too Well” held me during a painful of a person; “happiness” explains exactly what I teach in every creative writing class: Emotions need not exclude, but encapsulate, one another. We must know sadness to know joy. In “seven” Swift sings, “Before I learned civility/ I used to scream ferociously/ Any time I wanted.” It’s a clear allusion to Whitman’s line in “Song of Myself”: “I sound my barbaric yawp over the roofs of the world.” In the last song on

The Tortured Poets Department, “The Manuscript,” Swift concludes, “The story isn’t mine anymore.” Just as when a poet releases a poem into the world, the poem is no longer the poet’s; it belongs to the reader.

The poems in this collection now offer themselves to you—an invitation to be moved, as well as to engage. Each poem offers a puzzle to solve, because every poet wrote in response to a specific song. As you seek a poem’s shadow song, look closely at word choice. Poems, unlike prose, are short beings. Listen for words that allude to the lyrics of Swift’s songs. Swifties will find that while some poems easily reveal the song, others may take several readings. Some poets used individual words from the songs, without quoting lyrics for more than a word at a time. Other poets considered the theme of a song and responded with a like theme. A few did both. Either way, “Easter eggs” abound in this anthology. I even placed “Easter eggs” in the ordering of the poems. So look for how poems lead into one another. But, remember that whenever I felt it may become too obvious for Swifties, I played the villain and changed course. Most important, I ordered the book first and foremost to create an emotional arc. I had to keep Swift’s lyrics in one part of my mind and the poems in the other. It was like trying to cast—or maybe like falling under—a magic spell.