Excerpt

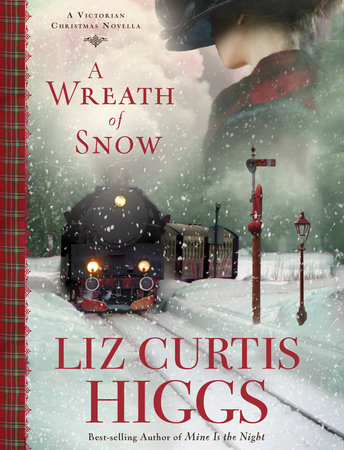

A Wreath of Snow

Stirling, Scotland

24 December 1894

In all her twenty-six years, Margaret Campbell had never been this cold. Shivering inside her green woolen coat, she passed the crowded shops of Murray Place as the snow fell thick and fast.

She could only guess when the next train would depart for Edinburgh. Why had she not consulted her father’s railway schedule posted by the kitchen door? Because she left Albert Place in tears. Because she left without even saying good-bye.

Meg lowered her chin lest a gust of wind catch the brim of her hat and wrench it from her head. Another minute and she would reach the corner. Two minutes more and—

“Mind where you’re going, lass!”

Startled, she nearly lost her balance on the icy pavement.

“Beg pardon, Mr. Fenwick.”

Her former schoolteacher, now bent with age, merely grunted in response.

“I’m Miss Campbell,” she reminded him, knowing how many students had passed through his classroom door. “Have you heard that I’m a teacher now? In Edinburgh?”

“Aye.” He stared at her for a moment, then tottered off without another word, the tip of his cane drawing a jagged pattern in the snow.

Meg turned away, slightly stung by the elderly man’s rebuff. Perhaps Mr. Fenwick believed unmarried women should reside at home with their families. If so, he was not alone in his opinion. But he didn’t know what life was like beneath her parents’ roof. I tried to stay, Mum. Truly I did.

Gripping her leather satchel, Meg headed toward Station Road, glancing at the shop windows with their mounds of fresh oranges and brightly colored paper bells. Her two dozen students would be home by now, celebrating Christmas with their loved ones. Just picturing bright-eyed Eliza Grant holding up her chalk slate covered with numbers and Jamie McFarlane shouting out the alphabet with glee renewed Meg’s confidence. She was living in the right place and doing the work she was called to do, no matter what the Mr. Fenwicks of the world might think.

The heavy snowfall muted the clatter of horses’ hoofs in the busy thoroughfare and washed every bit of color from the sky. Was it two o’clock? Three? She’d been so upset when she left her parents’ house that she hadn’t checked the watch pinned to her bodice or arranged for a carriage. Now she had to send for her trunk and hope it could be delivered to the railway station in time for her departure.

She turned the corner and was relieved to see a host of arriving passengers pouring into the street. It seemed the trains were running despite the weather. Easing her pace to manage the downward slope, Meg held out one hand, prepared to grasp a hitching post—or a stranger’s elbow, if need be.

Few pedestrians were moving in the direction she was. Instead, they were flowing upward into the town. Gentlemen returning home from the city, cousins gathering for Christmas, young scholars toting ice skates instead of books—all were tramping up snowy Station Road with joy on their faces. Guilt, as sharp as the wintry wind, swept over Meg. Her

parents had looked anything but joyful when she’d quit Albert Place. Her brother, Alan, was the reason she’d left, yet Meg had hurt her father and mother all the same. “Forgive me,” she whispered, wishing she’d said those words earlier.

For two long years she’d avoided a visit home, praying time might dislodge the bitterness that had taken root in her brother’s heart. But when she’d arrived in Stirling last evening, she’d discovered the sad truth. Alan Campbell, four years her junior, was even more churlish and demanding than she’d remembered and greedy as well, a new and unwelcome affliction. His parting words would follow her back to Edinburgh—to Thistle Street, to Aunt Jean’s house, to her house. “What a selfish creature you are, Meg.” She flinched even now, remembering the cruel look on her brother’s face and the sharpness of his tone. “You could have sold the house Aunt Jean gave you and shared the earnings with your family.”

You mean with you, Alan.

Meg lifted the hem of her coat and stepped with care through the slush and dirt the horse-drawn carriages left behind. She could hardly deny Alan’s needs were greater than her own. But when she’d moved to Edinburgh to care for their late aunt, wrapping her aching limbs with compresses and feeding her bowls of hot soup, Meg had never imagined Aunt Jean would choose to bless her only niece with the gift of her town house.

“Father should have been her heir,” Alan had insisted. Aunt Jean’s will, written in her neat hand, stated otherwise.

Over the midday meal Meg’s conversation with her brother had deteriorated into thinly veiled accusations on his part and tearful denials on hers, until she could bear no more. To be treated so unkindly, and on Christmas Eve! Her parents had tried to intervene, but Alan’s temper was not easily managed. Their patience with him was a testimony to their Christian charity. And to their love, though Meg wondered if guilt did not play an equal role.

Meg wove through the crowd and kept her head down lest someone recognize her and draw her into a discussion. Much as it grieved her, she had no polite banter to offer, no cheerful holiday sentiments. By tomorrow her mood would surely brighten. Just now she wished to tend her wounds in private. She stepped across the threshold into the railway station and brushed off the snow that clung to her coat, glad to be out of the wind. Inside the nearby booking office a cast-iron stove glowed with heat, steaming up the windows. But in the waiting area and across the broad, open platform, winter prevailed. Holly wreaths, their crimson berries bright against the dark green leaves, decorated the painted iron pillars supporting the roof. Everyone’s arms were filled with packages, as if Saint Nicholas had already come and gone.

Meg glanced at the clock mounted below the arched ceiling, then scanned the departure times posted for the Caledonian Railway. The southbound line, which stopped at Larbert, Falkirk, and Linlithgow en route to Edinburgh, departed at three twenty-six. Little more than an hour remained to collect her baggage.

When a middle-aged porter lumbered past, bearing a trunk far larger than her own, Meg hurried after him. “Sir, might I engage your services?” As he swung around with an expectant look on his face, she paused, her resolve flagging. How might her family respond when a porter asked for her belongings? Her mother would surely burst into tears. And her brother? He would probably want the contents of her trunk tossed into the street.

Determined not to lose heart, Meg reached for the small coin purse inside her satchel. “I’ve a single trunk to be transported from Albert Place onto the next train bound for Edinburgh,” she told the porter. She then informed him of the address and offered enough silver to guarantee his cooperation.

“I know the house, miss.” The coins disappeared into his pocket. “Soon as I deliver this trunk, I’ll see to yours.”

She sent him on his way, glancing up at the clock, hoping he would catch her meaning.

Hurry, hurry.

The queue at the booking window was blessedly short. Before she could join the handful of outbound travelers waiting to purchase tickets, a small dog appeared and began nipping at the hem of her coat. “Aren’t you a fine wee pup?” she murmured, bending down to stroke the young terrier. Even through her gloves she could feel his wiry coat and the light nip of his teeth as he playfully turned his head this way and that.

Above the din floated a high, reedy voice. “Can it be Miss Campbell come back at last?”

Edith Darroch. Of all the gossips in Stirling, she took the prize.

Meg slowly rose to face the woman, who served up savory news and idle rumors like a hostess offering scones and jam. Though Edith’s hair had faded to the color of ashes, her eyes were bright with interest.

“Mrs. Darroch,” Meg said. “Are you bound for Alloa to spend Christmas with your son?”

“Indeed not.” The older woman gave her terrier’s leash a swift tug. “Johnny is returning home for the holidays, as any loving child should do. I expect him on the next train.” After a cursory glance about the station, she asked, “Is your family not here to greet you?”

The question pierced Meg’s heart. Her parents had met her train last evening. But on this bitterly cold afternoon, she was very much on her own.