Excerpt

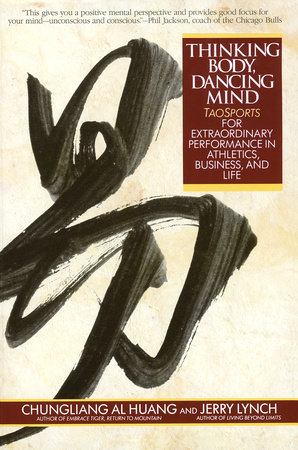

Thinking Body, Dancing Mind

AWAKENING TO THE TAO

The title of this book, Thinking Body, Dancing Mind, embodies a classic Tao paradox. It immediately encourages us to think differently by juxtaposing opposites. Ancient Taoist master-teachers often used paradox and metaphor to open up their students’ minds to new ideas, new awareness, and profound understandings of deep forces and unseen interconnections. Does the body, indeed, think? It does when you cease to interfere with its deep-seated intelligence, known as instinct or intuitive physical response. Does the mind dance? It does when you free it to flow with life’s natural processes, when you loosen your tendency toward critical judgment and control. A dancing mind is relaxed, visionary, and open to the full range of human possibility. “Thinking body, dancing mind” means that you have within you all that you need to be and to do anything you wish. The new attitudes and beliefs presented in this book will help you accomplish your goals and enjoy yourself in the process.

Part I enables you to begin your transformational journey by introducing you to the Tao and the concept of TaoSport. This process will lead you to extraordinary performance in athletics, work, and life. Here are guidelines—or TaoSports—for visualizations and affirmations for progressing along the way.

FROM WESTERN SPORTS TO TAOSPORTS

I brought my son Daniel to his first organized baseball game, a Little League game, when he was at the innocent and impressionable age of five. My intention was to expose him to the wonderful excitement and joy of neophyte little leaguers and their enthusiastic, proud parents. Daniel and I were both enjoying our outing, when a routine grounder was hit to first with the bases loaded. In most cases, such a hit surely would have ended the first inning. Instead, the ball rolled through the first baseman’s legs, and two runs scored. The subsequent behavior of the irate coach toward that vulnerable child killed Daniel’s and my desire to participate in that league. “Smith— play first for Stevens!” shouted the insensitive coach, who proceeded to embarrass the child with harsh criticism and took him out of the game.

Danny was shocked and confused; he wondered why anyone would want to play such a lousy game. Even at his young age, my son empathized with the boy’s pain. What Danny couldn’t know yet was the potential aftershock this incident could cause the heartbroken youngster, even well into adulthood: Would he ever try to play again after such humiliation? What messages about his sense of self would he internalize? What would this memory do to his confidence, self-image, fear of failure, and vision of what he could or couldn’t do in the future? Would he ever trust another coach? Would he ever play sports free of the anxiety and tension caused by this incident?

Unfortunately, this is not an unusual or isolated story. Most athletes in both individual and team sports experience from time to time tremendous pressure, fear, and anxiety generated by an overwhelming obsession to win. We learn this frame of mind from early childhood, and it is perpetuated by a competitive society that echoes with “the thrill of victory, the agony of defeat.” Athletic pressure is epidemic, and it spills over into other arenas of performance, particularly in the academic and corporate worlds. Such attitudes undermine the very core of our individual integrity and values.

A recent Sports Illustrated interview with the president of Allegheny College, Daniel Sullivan, addressed the impact of this obsession with victory, in a most powerful denouncement of college sports. “I cannot think of a single thing,” he stated, “that has eroded public confidence in America’s colleges and universities … more than intercollegiate athletics as it is practiced by a large faction of the universities in the NCAAs Division I and II. It is hard to teach integrity in the pursuit of knowledge or how to live a life of purpose and service, when an institution’s own integrity is compromised in the unconstrained pursuit of victory on the playing fields.” By contrast, the athletic department at Allegheny, he said, understands the role of sport in creating joy and fun while developing the athlete’s potential as a human being.

The Western approach to sports has given rise to questionable ethical and moral means of competition and standards of success. The use of anabolic steroids in Olympic games, professional sports, and other athletic arenas has been widespread in all countries. Violence and cheating in sport reflect the “win at any cost” attitude. This pressure to win has a more devastating effect on overall athletic performance than perhaps anything else. The same attitudes toward sport carry over to the world of business and everyday life, making us ineffective in those arenas of performance, too.

This Western approach is also responsible for creating a number of major nonproductive, dysfunctional behavior patterns in athletes. Having worked with thousands of professional, Olympic, university, and recreational athletes, ages ten to seventy-five, I have seen how the following behavioral patterns, reinforced by our culture’s competitive systems, stand in the way of their athletic and their personal joy, and their fulfillment and happiness in work and life in general. Most athletes today:

constantly struggle for external recognition rather than internal satisfaction;

measure their self-worth as an athlete or person solely on the outcome of their performances in sport, on the job, or in relationships of any kind;

focus on attaining perfection in every task, instead of seeing life as a journey in search of excellence;

treat their sport or goals as something to conquer, thereby expending valuable energy;

have unrealistic expectations that result in frustration, disappointment, and distraction;

blame others when things go wrong, and so feel out of control; and

condemn themselves for their failures, setbacks, and mistakes, and so have a poor sense of self.

Athletics are big business, and athletes’ well-being and health are often disregarded in the process. Athletes become statistics—living endorsements and walking billboards for corporate sponsors. A game’s outcome, the result—“Who won?”—has become everything, supplanting the notion that sport is about passion and love for what you’re doing.

In 1908, Pierre de Coubertin declared that “the goal of the Olympic Games is not to win but to take part.” We seem to have gotten off track since then. Biased broadcasters during telecasts of the Olympic games, feeling a loyalty to the United States, exhibit a nationalistic bit of joy in the setbacks and mistakes of our close competitors; flags at awards ceremonies have become instruments of alienation and separateness rather than unification. The results of our overweening desire to be number one are the stresses, anxieties, drug use, and dishonesty that plague our sports and our society. Krishnamurti once said, “War is but a spectacular expression of our everyday life.” So is sport an expression of our lives and attitudes.